A pretender to the Ottoman sultanate; A Greek priest seeking to drum up support for Christian interests in the Levant; a travel account bearing descriptions of songs sung on the streets of Constantinople regarding current events……. but let’s back up a bit.

Among the documents we find while looking for avvisi in the archive, are reports, not exactly newsletters, but mini-histories dedicated to specific events, going into some more detail than is customary in the weekly accounts, and covering longer time spans. Topics are usually of the sort that might catch the attention of the reader. Copies are made up and apparently distributed along the same routes as other manuscript news. Authors may be the same range of diplomats, literary figures, spies and adventurers that we find churning out the avvisi, but also individuals with a special knowledge of events needing to be diffused, or indeed, persons with a story of their own to tell.

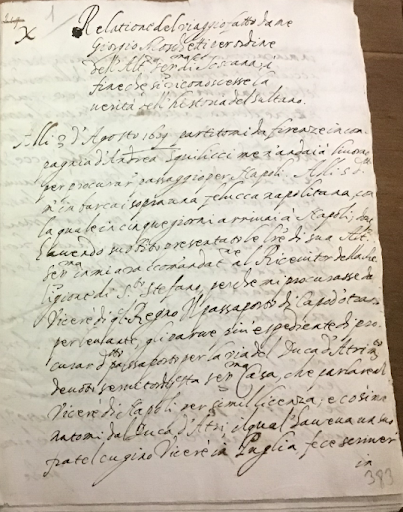

An example of the latter type is Giorgio Moschetti, a Greek priest from Candia who penned the "Report on the Trip Made by me, by order of His Most Serene Highness of Tuscany, in Order to Discover the Truth about the History of the Sultan" [Relatione del Viaggio fatto da me Giorgio Moschetti per ordine dell' Altezza Serenissima di Toscana, a fine di riconoscere la verita dell'historia del Sultano] located in a volume of dispatches, letters and newsletters from Constantinople. [MdP 4274, fols. 383 ff].

The report is not unknown. Carla Sodini cites it from the manuscript, in a chapter dedicated to “Imprese e progetti medicei per soccorrere con le navi quei poveri cristiani,” published in an anthology curated by Franco Salvatori entitled Il Mediterraneo delle citta: Scambi, confronti, culture, rappresentazioni (Viella Libreria Editrice 2011).

A printed transcription appeared in a work by Vittorio Catualdi entitled Sultan Jahja dell’Imperial Casa Ottomana od Altrimenti Alessandro Conte di Montenegro ed i suoi discendenti in Italia (Trieste: G. Chiopris, 1889), at pp. 517-33.

Apparently it was written to describe a trip taken to the Levant in 1609 under the auspices of the new nineteen-year-old grand duke Cosimo II, who had just taken power on the death of his father Ferdinando I and had already begun diplomatic maneuvers to join Christian princes in a common mission. On return to Florence in 1610 Moschetti pens this report, chronicling not only the story of his own misfortunes, including the capture and enslavement, but also the extraordinary episode of Sultan Jahja or Jachia (as he was variously called), the soi disant progeny of a minor wife of the deceased Sultan Murad III.

(Gino Benzoni, s.v. "Jachia," Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 61, 2004)

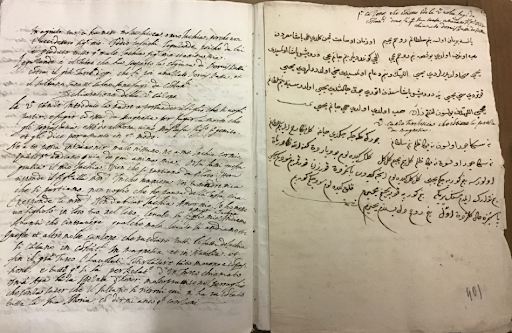

But what are these paragraphs at the end of the document with, as a coda, a text in Arabic purporting to convey a musical text? On the following page after the sultan’s story we are told that

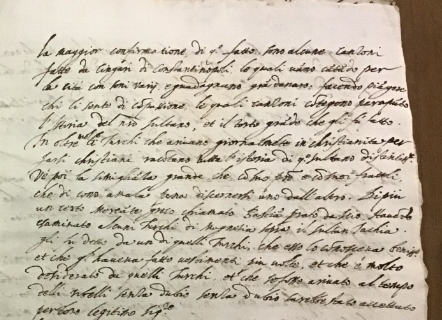

“The greatest confirmation of this fact are various songs made by the gypsies of Constantinople, who sing around the city with various instruments and earn much money, making the listeners weep from compassion, and these songs contain quite simply the story of our Sultan and the great evil that was done to him.”

[“La maggior confermatione di questo fatto sono alcune canzoni fatti da Cingari di Constantinopoli, le quali vanno cantando per la città con soni varii et guadagnano gran danaro; facendo piangere chi li sente di compassione, le quali canzoni contengono per appunto la Istoria del nostro Sultano, et il torto grande che gli fù fatto.]

The musical texts are described thus:

"The first Song in order contains the story of the Sultan's escape from Constantinople, the liberation of his life, which they were trying to end, and the death of the First Vizier called Dervis Bassa of Bosna killed for his sake."

[...]

"The second Song finds the mother trying to persuade her child to flee with her from Magnesia, in order to avoid the condemnation hanging over her, since Mustafa the firstborn son of the sultan was still alive."

The music itself is lost, but the words conjure up the same world of oral news transmission that was still prevalent in the Ottoman Empire by the late seventeenth century, according to recent work by J.-P.A. Ghobrial, The Whispers of Cities: Information Flows in Istanbul, London, and Paris in the Age of William Trumbull (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), inviting comparisons between news environments there and in Western Europe; on which we await confirmation in other documents yet to be examined.