by Davide Limatola

The appearance of handwritten news sheets known as avvisi in Italian, circulating through the chanceries and streets of European cities, even before the invention of printed newspapers, raises several important questions. One of these is what were the main themes of these handwritten news sheets?

Early modern information networks capture a great number of both major and minor events in the past. Mainly, the topics dealt with were daily events, diplomatic affairs, religious controversies, deaths of sovereigns, the execution of criminals and so on. But how does the situation change when the ordinary life of a country is shattered by a dramatic event such as a war?

The focus of avvisi shifts drastically to the war event and everything that revolves around it. The Siege of Vienna in 1683 could certainly be considered as one of the most important military conflicts to penetrate the fabric of the early modern information network.

Regarded as a real turning point in European history, the Siege represented not only a fundamental pushback at growing Ottoman hegemony on European soil, but also a renewed awareness of Christian forces. Handwritten avvisi and gazettes explored the event in all its aspects, recounting not only the most intense moments of the battles, but also the preparations, the anxieties and worries of the Christian world that saw its faith and welfare threatened by the advance of the “infidel army”.

The siege as an event has already been widely covered by historians in the 20th century, with authors such as John Stoye and Franco Cardini providing various perspectives on the siege, from the purely military, to its societal aspects. One element that has perhaps been underestimated, though, is the live reporting of the events, which we might call the "siege chronicle ".

An analysis of news distribution in the Holy Roman Empire and Italian Peninsula is one of the clearest methods of fully grasping the historical value of the siege.

The Florentine documents clearly show that the dissemination of news, to and from Vienna, was one of the main advantages the Emperor Leopold I had over Grand Vizier Kara Mustaphà.

However, the informative material spreading throughout Europe during the crucial days of the siege of Vienna included not only gazettes, avvisi and dispatches. There were also other media outlets circulating their material along the postal routes, and these were no less important or informative than the afore-mentioned documents.

In the summer of 1683, for instance, a series of news sheets circulated in Italy and Europe, whose aim was to predict the outcomes of the struggle with the Ottoman enemy through an accurate reading of the stars, the signs of the Zodiac, as well as through supernatural events. This was the case of a handwritten document in French that had wide circulation in Paris at the end of July 1683, and that on 3 August 1683 received an Italian translation by a correspondent of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany in France

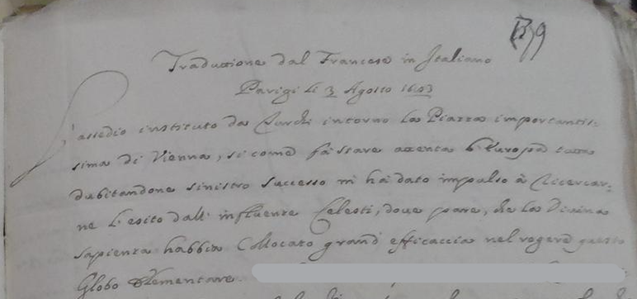

This document was anonymous, like the handwritten avvisi. It opens with the motivation that led the author to consult the stars, those bearers of information about kings and empires:

L'assedio instituito da Turchi intorno la Piazza importantissima di Vienna, si come fa stare attenta l'Europa tutta dubitandone sinistro successo mi ha dato impulso a ricercarne l'esito dall'influenze Celesti, dove pare, che la Divina Sapienza habbia Collocato grand'efficaccia nel regere questo Globo Elementare [The siege begun by the Turks around the very important city of Vienna, as it makes all of Europe watchful and worried about a possible sinister result, has encouraged me to ascertain its outcome from the Celestial influences, where it seems that Divine Wisdom has placed great efficacy in ruling this Elemental Globe]

In this handwritten document we discover why the imperial army had to endure the shock of the Ottoman attack (although without finally succumbing). This is attributed to the poor alignment of the stars, initially favourable to the Sultan, his Hungarian rebel allies and the allied Tatar army. There is no mention of the intrinsic strength of the enemy, nor of the lack of preparation of the Christian army.

Of course, this is an expedient that has always been used in military propaganda: it was not unusual to undermine the morale of the enemy in battle, particularly an enemy as antithetical to the Christian soldier as an Ottoman soldier.

In these documents, drenched in Christian rhetoric, the Turk is the living representation of the villain. The Turk will always be portrayed as the reverse of the Christian hero, that is the champion of chivalrous values and Christian morality. Consider the representation of General Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg, one of the leaders of the imperial army. In the documents, he is represented not only by his military qualities, but also by his clemency and Christian values. In one of the Venetian documents preserved in the State Archive of Florence, the General grants the Turks a respite to bury their dead, but, in agreement with the depiction of the treacherous and disloyal Turk, the Janissaries try to take advantage of the situation to counterattack.

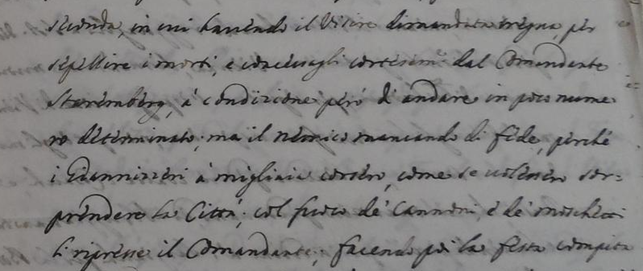

The newsletter describes a case of deception where the allies were led into a false sense of security,

[…] avendo il Visir [Mustafa, Kara Merzifonlu (Pasha)] dimandata tregua, per seppellire i morti, e concessagli cortesemente dal Comandante Staremberg [Starhemberg, Ernst Rudiger von], a condizione però di andare in poco numero determinato; ma il nemico mancando di fede perché i Giannizzeri a migliaia corsero, come se volessero sorprendere la Città; col fuoco de' Cannoni, e de' Moschetti li represse il Comandante. [the Vizier [Mustafa, Kara Merzifonlu (Pasha)] having asked for a truce, to bury the dead, and having it kindly granted by Commander Staremberg [Starhemberg, Ernst Rudiger von], on condition, however, of proceeding with a reduced and pre-determined number; but the enemy showed bad faith, the Janissaries in their thousands running forward, as if to surprise the City; thus the Commander surprised them with Cannon- and Musket fire].

In other passages, there are not only some vague references to the motion of the stars, but also descriptions of horoscopes.

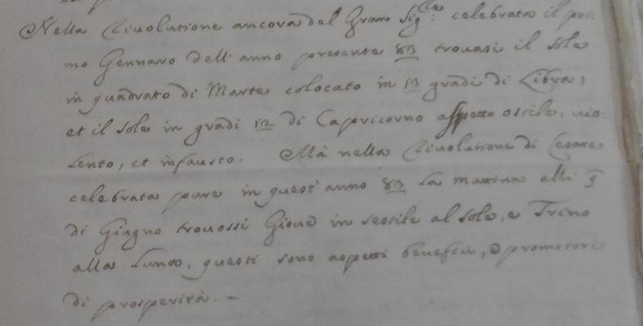

Regarding the figure of Mehmet IV we read that:

Nella Rivolutione ancora dal Gran Signore, celebrato il primo Gennaio dell'anno presente 83, trovasi il Sole in quadrato di Marte colocato in 13 gradi di Libra, et il Sole in gradi 12 di Capricorno aspetto ostile, violento, et infausto. [Also, the Revolution of the Grand Turk, celebrated the first January of the present year 83, the Sun was found in the House of Mars placed in 13 degrees of Libra, and the Sun in degrees 12 of Capricorn with a hostile, violent, and inauspicious aspect].

Very different is the future foreseen for Leopold I, Christian Emperor:

Quando poi il Sole arrivava precisamente alla notata linea della duodecima Casa, il che si attende in due anni in circa, all'hora si vedeva cresciuta la possanza fortuna dell'Imperatore Christiano, e sminuita respettivamente quella del Turco se a ciò condescendeva la providenza Divina. […] nella Rivolutione di Cesare celebrata prima in quest'anno 83 la mattina alli 9 di Giugno trovossi Giove in sestile al Sole, e Trino alla Luna, questi sono aspetti benefici, e promotori di prosperità. [When then the Sun arrived precisely at the noted line of the twelfth house, which is expected in about two years, then the power of fortune of the Christian Emperor will be seen to have increased and that of the Turk diminished, if Divine Providence condescended to this. [...] in the Revolution of Caesar celebrated first in this year 83 on the morning of June 9 I found Jupiter in sextile to the Sun, and Trine to the Moon, these are beneficial aspects, and promoters of prosperity].

Instead, a bright future seems to await Leopold, although this seems difficult to achieve. The expectation is that in about two years, the strength of the Turks will have decreased exponentially.

The language used in these documents is dense with technicalities, aimed at beguiling the reader who is not accustomed to hearing about Trigons, Astral Houses, Zodiacal Arcs and Semi-Arcs.

An aspect that we have to highlight is not just the content, but rather the forms in which particular information was delivered.

In Early modern times, to get a complete picture of the fabric of information, we cannot ignore how many manuscripts, gazettes, and specialised material, such as the avvisi, circulated throughout Europe. A Parisian astrologer, even without aid of the printing press, could have the good fortune to be read in Florence and in many other parts of the Old Continent, influencing the minds of his readers.

The power contained in documents like the Parisian one should not be underestimated. The circulation of information was one of the most impactful elements in the Christian victory in Vienna, no less than the military efforts of the men fighting in the field.

The Christian triumph was above all a victory in the field of information thanks to the perseverance of postmasters and informers travelling the roads around Vienna. The absence of a stable circuit through which news could circulate was one of the Turks' main problems at the gates of Vienna. The Sultan, who remained far from the battlefield in Belgrade, was often informed after the assault had taken place and could not keep his eye on the situation as the allied troops comprised of the forces of the King of Poland Jan Sobieski and Emperor Leopold were able to do. It is therefore necessary to reconsider the world of information not only as a resonance chamber of events, but also as acting subjects within the historical event. To do this, we need to analyse not only the documents closely connected to the battle narrative, but also all that material that seems to be marginal, but which inevitably ended up influencing contemporaries. Astrological prophecies and narrative referring to the occult were an important part of early modern news culture.

FURTHER READING

Franco Cardini, Il Turco a Vienna. Storia del grande assedio del 1683, Roma-Bari, Laterza, 2011.

Mario Infelise, Prima dei giornali, Roma-Bari, Editore Laterza, 2005.

Ornella Pompeo Farcovi, Scritto negli astri. L'astrologia nella cultura dell'Occidente, Venezia, Marsilio, 1996.

Ornella Pompeo Farcovi, Lo specchio alto: astrologia e filosofia fra Medioevo e prima età moderna, Pisa-Roma, Fabrizio Serra editore, 2012.

Giovanni Ricci, I Turchi alle porte, Bologna, Il Mulino, 2008.

John Stoye, L’assedio di Vienna, Bologna, Il Mulino, 2011.

Andrew Wheatcroft, The enemy at the gate. Habsburgs, Ottomans and the battle for the Europe, New York, Basic Books, 2008.

Davide Limatola is Junior Research Fellow in the Euronews Project, where he participated in the internship program coordinated by Dr. Davide Boerio. During his appointment, he carried out research which resulted in his MA thesis entitled: Avvisi manoscritti e gazette a stampa: religione e diplomazia nelle carte medicee sull’Assedio di Vienna (Handwritten avvisi and printed gazettes: religion and diplomacy in the Medici documents on the Siege of Wien) and discussed in July 2021 at the Department of History of the University of Naples Federico II, obtaining the highest marks (110/100 cum laude). He has also been awarded with a generous fellowship granted by the Director Alessio Assonitis for attending the 2021 Summer Paleographic and Archival Seminar at the Medici Archive Project in Florence. He is currently preparing a PhD project proposal on the European media ecosystem seen through the siege of Wien.