By Brendan Dooley and Andrea Di Carlo

Politics on campus? Sometimes of the most serious sort! Consider this report on discussions within the Jesuit College in Madrid in the age of Philip IV, as reported in a newsletter dated April 3, 1638:

“In this College of the Jesuit Fathers, before finishing the Lenten lessons, and beginning the Holidays, Political Debates were held, dedicated to the Grand Prince, son of His Majesty, which were attended by the three Cardinals who are in Madrid, that is, Borgia, Spinola and Moscoso, some bishops, grandees and principal lords, since the speakers and disputants were of quality. The first question was, who had more love, the Prince for the vassal, or the vassal for the Prince”

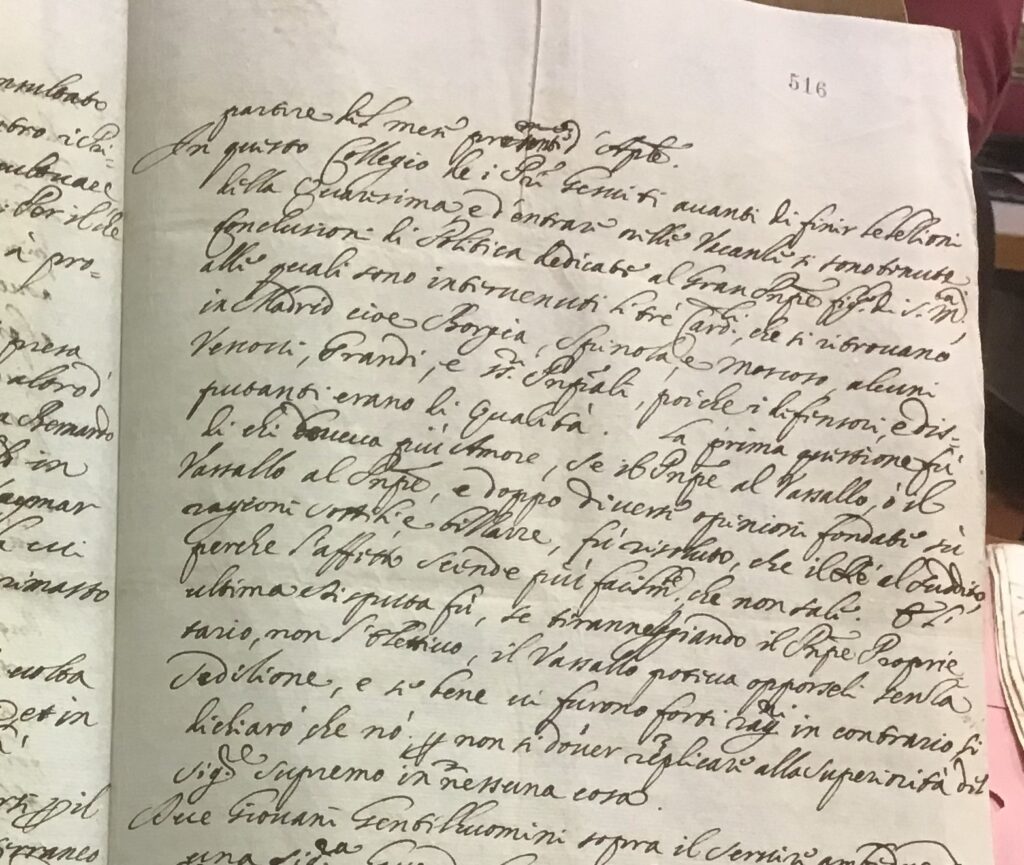

ASFI, MdP vol. 5078, c 516r. di Madrid, 1638 / April / 3

The verdict? Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised to find that, in the age of Galilei, at least according to the version of this Italian account, a question of dynamics–fluid or solid–enters in:

“after various opinions based on subtle and bizarre reasons, it was resolved that the King [had more love] for the Subject, because affection goes downwards more easily than upwards."

Another question involved a far more momentous matter, and a standard one in textbooks on politics and the state, which will eventually take us down a path that reaches as far as John Milton’s England. To what lengths can a people go, in the presence of a bad king? Here is how it is described:

“And the last dispute was whether, the hereditary Prince, not the Elective, acts tyrannically, the Vassal could oppose them without compunction.”

The timing was particularly crucial, considering that rebellious tendencies were already manifested in Portugal in 1638 (relevant Featured Post on the way) prior to the break from Spain that would take place two years later, followed elsewhere in the Spanish empire and around Europe, including England, by ten more years of popular rebellions and revolts.

Another predictable outcome? We hear that “although there were strong reasons in the affirmative, it was resolved in the negative; so that the superiority of the Supreme Lord cannot be questioned in anything.”

But monarchical absolutism was not as safe as the debate made it seem, even in the theoretical realm.

At least on this point we have to agree with Michel Foucault, that the early modern age laid bare the problem of government. This is the case because the political landscape was upset by theorists as diverse as Machiavelli and the Monarchomachs.

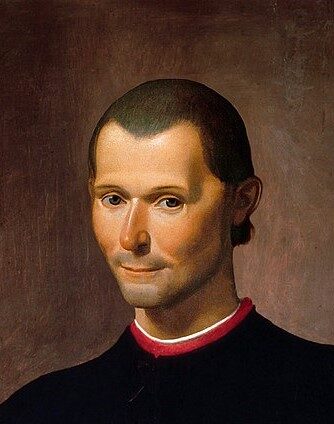

portrait of Machiavelli by Santi di Tito (1536–1603), now in Palazzo Vecchio, Florence

Machiavelli’s political oeuvre was informed by his first-hand knowledge of politics. He critiqued the Aristotelian notion of virtue as a golden mean. On Machiavelli’s account of virtue, virtues are not compromises between two extremes, but one should instead retrieve the real meaning of virtue. Accordingly, being virtuous involves behaving like a vir, the strong and courageous leader of ancient Rome. In The Prince (completed in 1513 but published posthumously in 1532), the politically astute Machiavelli recommends that his would-be leaders should be like the fox and the lion, violent but cunning. Therefore, leaders are no longer supposed to strike a balance between two extremes; they are supposed to do the opposite as the survival of the state is at stake. The author recommends that leaders focus on “la verità effettuale della cosa (“the effectual truth of the matter”). It is not a stretch to argue that Machiavelli would envisage killing a sovereign who goes beyond the stipulations of society.

Long after Machiavelli was in the grave and his works placed on the Index of forbidden books, a war-torn France looked at novel ways when dealing with politics. The clash between Huguenots and Roman Catholics meant that a Roman Catholic sovereign was no less controversial than a Protestant one. At this point, in come the Monarchomachs. They believed that an illegitimate ruler should always be deposed. In the Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos (1579), the most notorious Monarchomac treatise, the author, Philippe de Mornay, answers the question “may a prince who oppresses and devastates a commonwealth be resisted; and to what extent, by whom, in what fashion, and by what principle of law?” His answer:

“A king who violates the compact […] persistently is truly a tyrant by conduct. In this case the officers of the kingdom are obliged to pass judgment on him according to the law and, should he resist, to expel him from office forcibly where other means do not avail.”

According to this view, even though fulfilling a very important official role, sovereigns cannot behave in such a way that they flout the law of the country. Should this come to pass, then the appropriate response is regicide. This is very different from the Aristotelian understanding of government: no longer is a compromise struck up, but the subjects are now allowed to take matters into their own hands.

Monarchomach theories soon gained prominence outside France, although the country where they most strongly influenced the political debate was not Spain but Britain. Their ideas came to the fore during the reign of Charles I, whose father, James I, had claimed to be the human representative of God but formed a peaceful relationship with the Puritans. No such compromises were possible under Charles, however, and he did his best to make the Puritans upset to the extent that they viewed his Church of England as a crypto-Catholic institution. The king, who had been sentenced to death by Parliament, rebutted the accusations of being a covert Roman Catholic in his book Eikon Basilike (1649, “The Image of the King”). Therein, he defended his commitment to the Church of England and his religious policies.

However, one of the king's most vocal opposers, John Milton, rejected his argument in a tract called Eikonoklastes (“The Destroyer”, 1649).

There, Milton argues that Charles is a “politic contriver” who “certainly would have the people come and worship him”. Charles is the idol, the crypto-Catholic thing that has to be destroyed. The words here echo the words of Vindiciae. The sovereign who violates the sacred compact with the subjects, exercises “Tyrannical proceedings” and therefore must be brought to justice.

The Spanish Jesuits would have strongly disagreed!