by Brendan Dooley

Who has not heard of Dracula, gothic classic of vampire lore par excellence? What about The Mystery of the Sea? The latter book by the same author received far less acclaim. To be sure, books were not this Irish author’s only stock in trade. By the time Bram Stoker published his famous work he was already nearing the end of a long mostly unrelated career in theater promotion and management which had brought him in contact with English as well as American high society. As a writer, his experience also included theater reviews for a Dublin newspaper. Arguably, all these aspects, and much else besides, find their way somehow into the novels; but that is not our concern here.

Reading through The Mystery of the Sea we find some curious elements from the standpoint of the history of news, with a particular emphasis on memories regarding the sensational sailing and destruction of the Spanish Armada which occupied readers from May to September 1588, a serious setback for advancing Spanish hegemony in Europe in those days. What did the events signify to readers, not only at the time, but three hundred years later, at the end of the nineteenth century?

That King Philip II’s Great Enterprise could have left such a long shadow seems hardly surprising, considering that it was the media event of its day. Reports, true and false, flew back and forth and among the states of Europe along with calculations concerning the possible size of the fleet, the time and place of departure, the itinerary, the possible conflicts in the Channel and elsewhere. Victories were announced and denied, as were eventual defeats. The tragic last phase including the chase along the coast and around Scotland all the way to the southern shores of Ireland in terrible weather, was a daily preoccupation in the news (in spite of transmission times ranging from a week to a whole month) long before it became the stuff of legends.

[portrait of Philip II by Sofonisba Anguissola, Prado Museum (Wikimedia)]

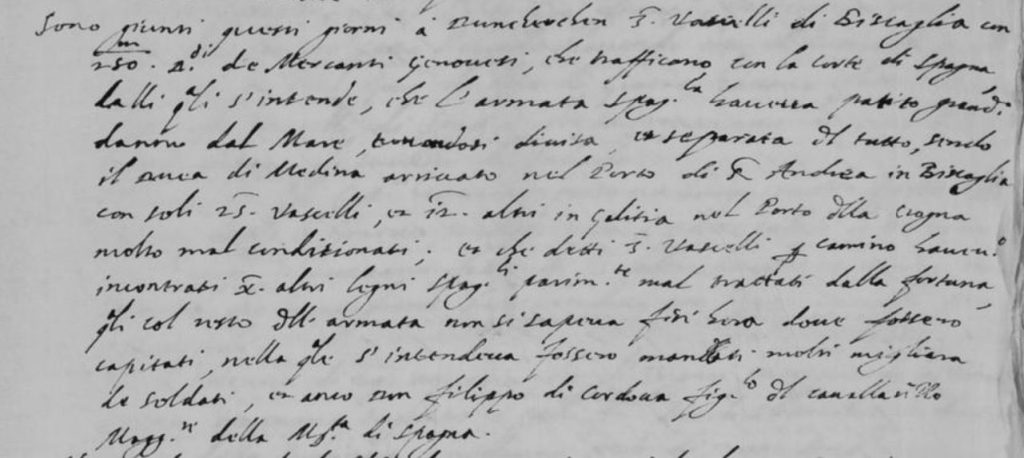

For instance, consider this report from Antwerp about news brought in by ships from Spain.

“It is understood that the Spanish Armada has suffered great damage from the sea, being divided and separated entirely, with the Duke of Medina having arrived in the port of S. Andrea in Biscay with only 25 vessels and 12 others in Galitia in the port of Corunna in very poor condition; and that … 10 other Spanish ships [were] equally mistreated by the weather, and along with the rest of the army it was not known where they had ended up, but it was understood that many thousands of soldiers were missing including Don Filippo di Cordova son of the Major Horseman of the Majesty of Spain.”

S'intende che l'armata spagnola haveva patito grande danno dal mare, trovandosi divisa et separata del tutto, sendo il duca di Medina arrivato nel porto di S. Andrea in Biscaglia con soli 25 vascelli et 12 altri in Galitia nel porto della Crogna molto mal conditionati; et … 10 altri legni spagnoli parimenti [fossero] mal trattati dalla fortuna, quale col resto dell'armata non si sapeva fin ora dove fossero capitati, nella quale s'intendeva fossero mancati molte migliaia de soldati et anco Don Filippo di Cordova figlio del Cavallarizzo Maggiore della Maestà di Spagna.

The Mystery of the Sea is set in Cruden Bay, on the East coast of Scotland in Aberdeenshire, a maritime retreat where Stoker went to write and relax, eventually settling there. Archibald, the main character in the novel, enjoys taking long walks along the coast, but one evening he sees a surreal spectacle:

“Up the steep path came a silent procession of ghostly figures, so misty of outline that through the grey green of their phantom being the rocks and moonlit sea were apparent, and even the velvet blackness of the shadows of the rocks did not lose their gloom. And yet each figure was defined so accurately that every feature, every particle of dress or accoutrement could be discerned. Even the sparkle of their eyes in that grim waste of ghostly grey was like the lambent flashes of phosphoric light in the foam of moving water …

“A vast number of the phantoms had passed when there came along a great group which at once attracted my attention. They were all swarthy, and bore themselves proudly under their cuirasses and coats of mail, or their garb as fighting men of the sea. Spaniards they were, I knew from their dress, and of three centuries back. For an instant my heart leapt; these were men of the great Armada, come up from the wreck of some lost galleon or patache to visit once again the glimpses of the Moon. They were of lordly mien, with large aquiline features and haughty eyes. As they passed, one of them turned and looked at me. As his eyes lit on me, I saw spring into them, as though he were quick, dread, and hate, and fear.”

What a vision for the curious observer!

No spoiler here about how the strange experience fits with the rest of a complicated plot involving encrypted letters and an attempt by Pope Sixtus V to ensure that the English might be returned to the Catholic fold. Our inquiry concerns the way in which actual events somehow enter the collective memory and become elements to reckon with in formulating yet other stories. From this standpoint, the Armada story is one among many that we are attempting to interpret, and we still have a long way to go!

with thanks to Jason McElligott and Theodore Kocher

FURTHER READING

S. Arata (1990). The occidental tourist: Dracula and the anxiety of reverse colonization. Victorian Studies 33(4), 621-645.

J. Valente (2001). Dracula’s crypt: Bram Stoker, Irishness, and the question of blood. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Jason McElligott (2019). Bram Stoker and the Haunting of Marsh's Library. Dublin, Marsh's Library.

Colin Martin, Geoffrey Parker (1988). The Spanish Armada. London, Hamish Hamilton.

De Lamar Jensen (1988). The Spanish Armada: The Worst-Kept Secret in Europe. The Sixteenth Century Journal 19 (4), 621-641