By Brendan Dooley

Baccio Giovannini, the Florentine resident in Paris, writing on 10 June 1602, goes straight into detail:

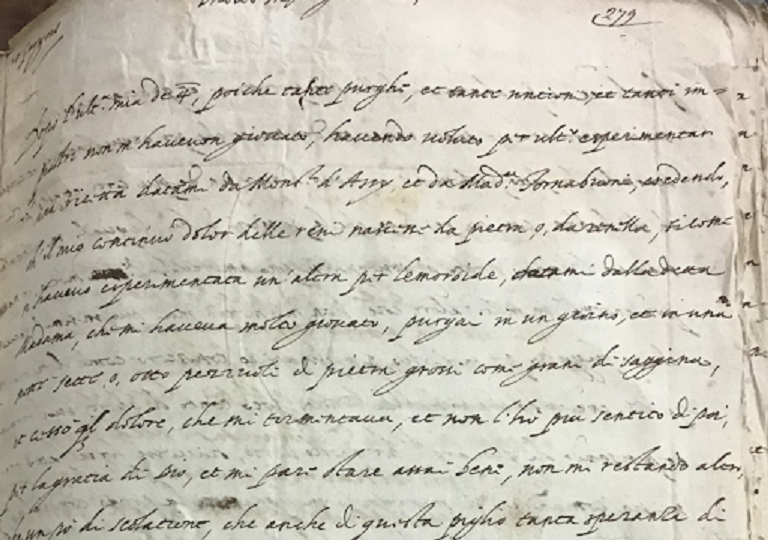

“My Most Serene Lord and Patron: After my last letter on the fourth, since so many purges and ointments and poultices did nothing for me, I finally decided to try a recipe I got from Monsignor d’Assy and Madame Tornabuoni, thinking that my constant kidney pain came from the stones or from urinary gravel, whereas I had already tried another one for hemorrhoids from this Madame, which worked very well, so I purged in a day and a night seven or eight pieces of stone as large as sorghum seeds, and my suffering ceased, and I have no longer felt it thank God, and I feel very well, with only a bit of draining, and I have high hopes of freeing myself from this too.”

MdP 4615a fol. 279r

Exactly what impression these words may have made on Grand Duke Ferdinand I, is not yet known. But the immediate purpose is easy enough to guess– because our writer practically spells it out, with all the deferential subtlety we expect from a career diplomat: he wants to retire!

He goes on: “Indeed, so desperate was I about ever getting rid of that dull affliction of the kidneys and therefore being able to better serve my Most Serene Master, that I requested permission to convalesce and finally die at home. But if Your Highness, knowing now that I am well, does not grant me this, he is the master, and I am the servant, most obedient in everything I am able to do, but where I am unable, I know You are most discreet and would not force your servants to do what nature forbids them.”

Baccio’s seemingly brilliant tactic of bringing up a delicate topic by reference to still another delicate topic seems alas to have failed, since he stayed on in Paris as the Grand Duke’s representative until 1607, without any notable respite.

But what concerns us here is not Baccio’s career per se, adequately covered in the detailed entry by Stefano Calonaci for the Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (Volume 56, 2001), except insofar as the letter, in the light of the biography, illustrates the practice of a kind of intimacy without intimacy, seizing a common theme as a way of communicating familiarly across the status divide.

Indeed, here we find that illness is a social affair. Even in the procurement of medicines and unguents, the writer is building his networks and reminding those he knows that they too might share their thoughts with him. Nothing is off limits, he seems to imply.

Of course, the social history of medicine is made of such stuff. Let us recall Fulgenzio Micanzio’s Life of Paolo Sarpi (1646), where hemorrhoids become a way of talking about the character of his subject, a counselor to the Venetian Republic.

“He had three great illnesses that were, in a way, congenital, and followed him to the grave: a hepatic fluxus, a prolapse of the large intestine, and periodical headaches, apart from the difficulties from hemorrhoids” all of which he nonetheless “put up with in good humor and deeply felt serenity, as though he were the healthiest person in the world.”

In regard to urinary stones, on the other hand, Ahmet Tefekli (2013) points out that “The roots of modern science and history of urinary stone disease go back to the Ancient Egyptians and Mesopotamia.” Indeed, “The first recorded details of “perineal lithotomy” were those of Cornelius Celsus. Ancient Arabic medicine was based mainly on classical Greco-Roman works. Interestingly, the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 forbade physicians from performing surgical procedures, as contact with blood or body fluids was viewed as contaminating to men.”

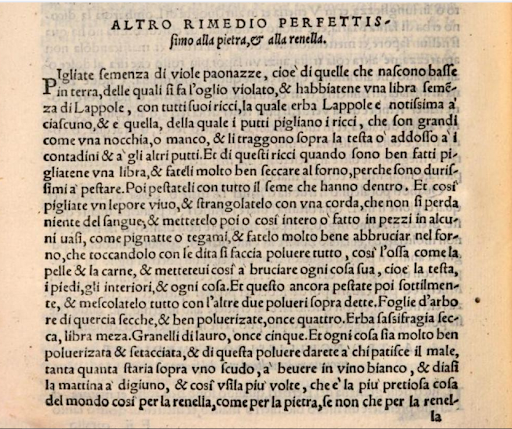

Given the wide diffusion of such problems, how did people deal with them in the early seventeenth century, other than by the unnamed substances mentioned in Giovannini’s letter to the Grand Duke? Here is a typical recipe from the much-reprinted manual by Girolamo Ruscelli, writing under the pseudonym Alessio Piemontese, whose Dei Segreti..., first issued in Venice (eredi di Marchiò Sessa, 1557), with instructions on everything from curing snake bites to removing arrows from a body, to quieting children affected by the “moon sickness” (details in another post!). He calls it “Another most perfect remedy for the stone or for renella.”

….Take the seeds of red violets, i.e. those which hide low in the earth, of which they make violet oil, and take a pound of the hops plant, with all its curls….. And take a live hare and strangle it with string such that it loses no blood, and place it either whole or in pieces in some containers, such as pots or pans, and burn it well in the oven, so it disintegrates into dust at the touch, both the bones and the skin and meat, and burn everything of it, i.e., the head, feet, innards, and everything. This you mash very finely and mix with the other above ingredients, four ounces. Dry saxifrage, a half pound. Grains of laurel, five ounces. And everything very well pulverized and strained, and give as much of this powder to the patient as would stand upon a scudo, to be taken in white wine in the morning on an empty stomach, repeat several times, and it is the most precious thing against renella and the stone…

Mentioned in the recipe and first identified by Andrea Matthioli (1501 – c. 1577), the Matthiola incana, also known as the Violacciocca, was well known for medicinal properties; and likewise the Humulus lupulus (hops). Animal sacrifice for medical purposes we will cover in another post. But apart from the concerns of a moment and the search for a medicine, the discourse about pain may also refer to timeless aspects that tie our world to the past. Does a general refusal to recognize the inherent precariousness of lives and loves constitute one of the central contradictions of existence? Tobin Siebers (2013) thinks so. Maybe the bearer of such personal information seeks to lessen the burden by reminding about a shared predicament more often experienced than articulated. Isn’t this another role of news?

NOTE: Thanks to Mario Infelise for helpful suggestions

FURTHER READING

Stefano Calonaci, s.v. “Giovannini, Baccio,” Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (Volume 56, 2001)

Health, Disease and Society in Europe, 1500-1800: A Sourcebook. Front Cover. Peter Elmer, Ole Peter Grell. Manchester University Press 2004

Ahmet Tefekli and Fatin Cezayirli, “The History of Urinary Stones: In Parallel with Civilization” Scientific World Journal; 2013: 423964. Published online 2013 Nov 20. doi: 10.1155/2013/423964

Roselyne Rey, The History of Pain. Tr. Louise Elliott Wallace, J. A. Cadden, S.W. Cadden, Harvard University Press, 1998

Tobin Siebers, “Disability and the Theory of Complex. Embodiment—For Identity Politics in a. New Register,” in The Disability Studies Reader, ed. Lennard J. Davis, Routledge, 2013.