By Brendan Dooley

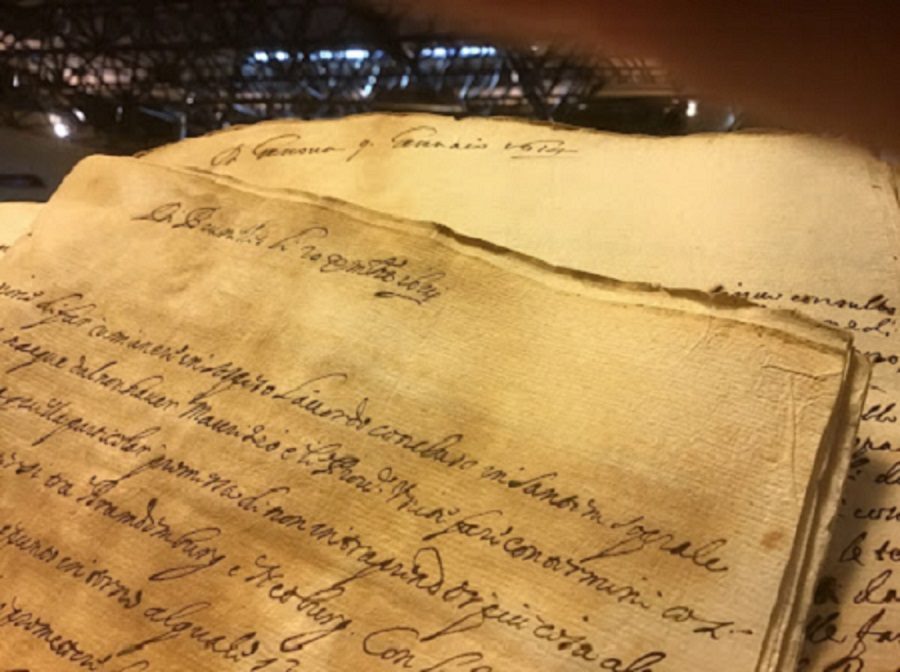

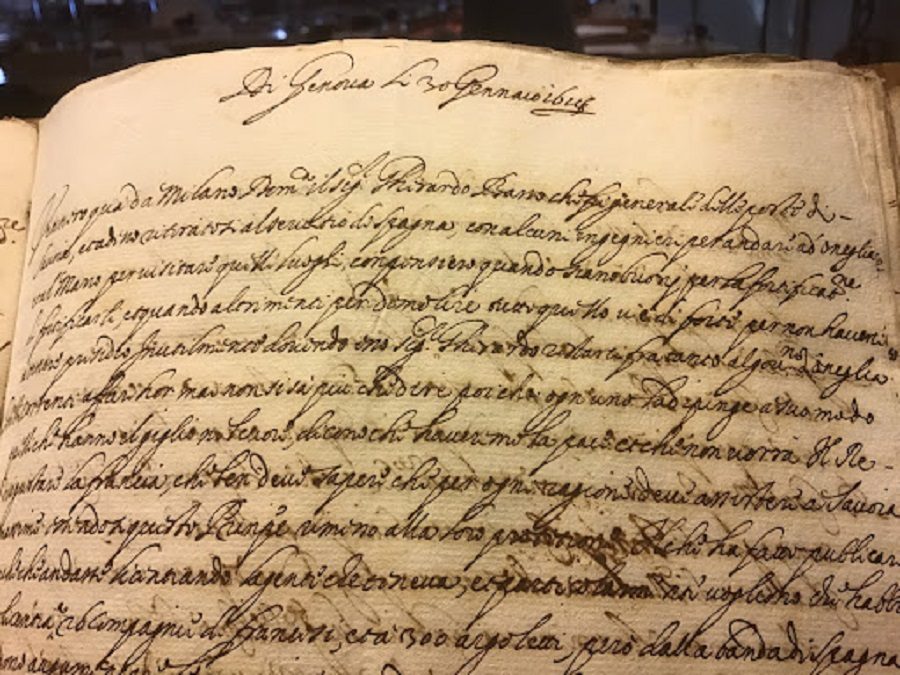

Mediceo del Principato, vol. 2861. Unpaginated, but bound tightly enough so as not to confuse the order of pages. Leafing through, we find the order of pages seems somewhat idiosyncratic. Why is “From Bruxelles the 20th of December 1614” followed by “From Genoa, 9 January 1614," although the progression of dates up to 20 December otherwise seems perfectly chronological?

Did the compiler of the volume blink while sorting and binding the pages? More probably, he sorted the pages according to early modern criteria regarding the start of the year– which did not always occur on the first of January!

In fact, until the eighteenth century numerous systems were in use, of which the following is a short list:

NATIVITY STYLE sets the first day of the year to December 25th.

INCARNATION STYLE sets the first day of the year to 25 March, used in Tuscany until 1749, and elsewhere

VENETO STYLE , is fixed on March 1st

BYZANTINE STYLE According to this style, the year begins on September 1st

CIRCUMCISION STYLE is the current system, although in fact, well before that time, the Julian calendar stipulated for the year to begin on January 1st.

Looking at the same archival volume (2861) a little further on in January: The writer apparently can’t decide! He’s put in 1614 and corrected it to 1615 (or, did he put 1615 and, for a scruple about attachment to older styles of dating, correct it to 1614?). Here:

To resolve such questions, when studying the compilation of the volume doesn’t help, we might look at the information itself, to see if there are other testimonies dating the substance this way or that.

Comparing the various volumes and newsletters, we are reminded that reckoning of the new year was subject to different traditions from place to place. In France as well as in the Low Countries, Germany and much of Italy, no Gregorian reform was required to force observance of the first of January. On the other hand, nothing could persuade the Venetians to move the Venetian new year two months back from the date inherited from the Roman Republic, the 1st of March. In Tuscany, England and Scotland, on the other hand, the Julian vernal equinox (or feast of the Annunciation), 25 March, continued to prevail, while Russia began the year on the day of the Creation (1 September). So gaining a sense of exactly when things were happening was no simple matter—in fact, it was a skill that went along with travel and every other form of intercity and interstate communication.

Indeed, whether it was actually a holiday on one side in a battle or a simple weekday on the other side could affect the humors involved, and incidentally also the outcome of a battle (Hiram Morgan has considered the social and military consequences of calendar differences).

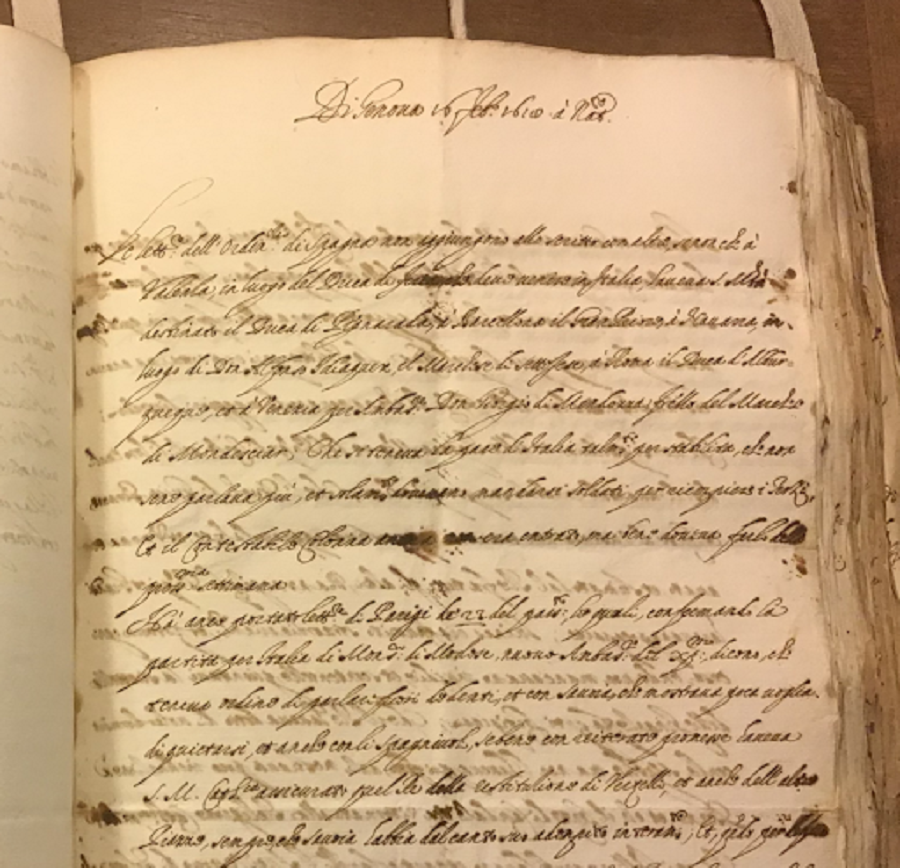

Occasionally the writer helps us in our inquiry, as in the following case dated 16 February 1618, where we are told the calculation is “Nativity style,” so the year began on the previous 25th of December:

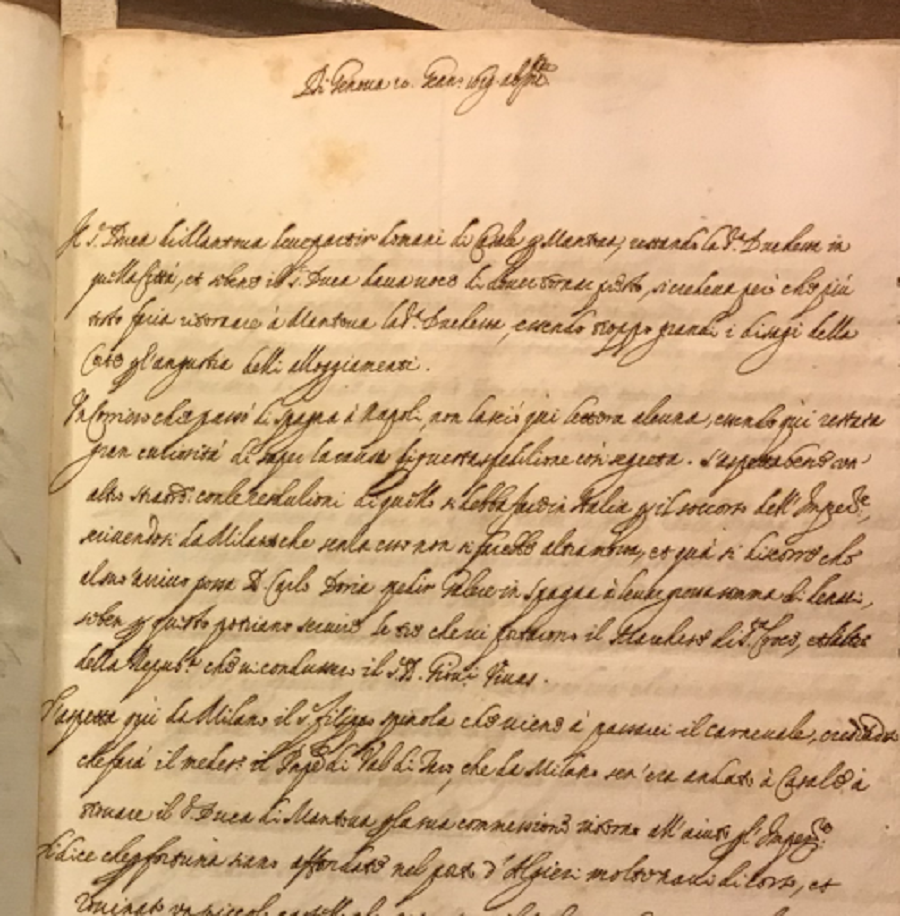

In the following example, dated 10 January 1618, we are informed that the dating is “Ab Incarnatione,” so the year 1619 won’t begin until 25 March.

Clearly, bringing in the new year was no easy matter; but with a little study we can find out what year it is!

FURTHER READING

Hiram Morgan, “The Pope’s new invention: the introduction of the Gregorian calendar in Ireland, 1583-1782” (unpublished paper at “Ireland, Rome and the Holy See: History, Culture and Contact,” a UCC History Department symposium at the Pontifical Irish College, Rome, 1 April 2006), https://www.academia.edu/209971/The_Popes_new_invention_the_introduction_of_the_Gregorian_calendar_in_Ireland_1583_1782?source=swp_share consulted on Jan. 26, 2022

B. Dooley, Introduction, in B. Dooley, ed., The Dissemination of News and the Emergence of Contemporaneity in Early Modern Europe (Ashgate, 2010).