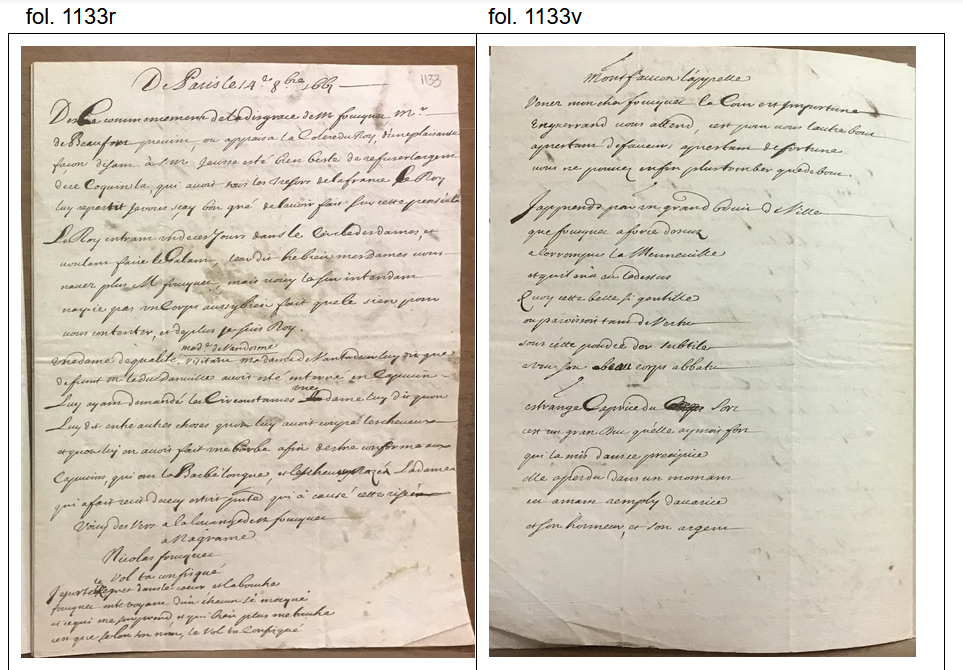

When the newsletter breaks into verse, we must be in the court of the Sun King! There at least, or close by, is where this Paris newsletter originates, now conserved in Mediceo del Principato vol. 4891. The year is 1661 and the vast riches accumulated by Louis XIV's Finance Minister Nicolas Fouquet are attracting attention, especially since the estate at Vaux le Comte seems to rival Versailles. Where is the money coming from?

In Medici Archive Project database: https://mia.medici.org/Mia/index.html#/mia/document-entity/54833#tr_558728_30216

By our newsletter’s time of writing the disgraced minister was already under arrest, having offered the king his estate at Vaux in a futile appeal for favor.

The whole era of early French Classicism has been celebrated and memorialized by poets and prose stylists in and around the court, including Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux, Jean Chapelain, the abbé Charles Cotin, Philippe Quinault, Georges de Scudéry, Molière, La Fontaine and others. Our writer, and the writings included here, are all anonymous.

Ministers are fair game for satire, mostly when they are in trouble; and we begin in the middle of the story. The duc de Vendôme (M. de Beaufort) is in conversation with the king, and they agree: Fouquet had to go. The newsletter begins,

“From the start of M. Fouquet's disgrace, M. de Beaufort, prevented or appeased the king's anger, in an amusing manner, telling His Majesty I would have been quite stupid to refuse the largesse of this rascal, who had all the treasures of France. The King replied, I am grateful to you for having done so.”

[Dès le commencement de la disgrace de Monsieur Fouquet, Monsieur de Beaufort, prevint, ou appaisa la Colère du Roy, d'une plaisante façon, disant a Sa Majesté j'eusse esté bien beste de refuser largesse de ce Coquin la, qui avoit tous les Tresors de la France. Le Roy luy repartit je vous sçay bon gré de l’avoir fait sur cette pensée-la..]

Next we move into the area of court gossip, and there is a putative conversation where the king engages in banter regarding his famously elegant physique.

“The king entering the ladies' circle one day, and wanting to play the gallant, tells them: ‘very well, ladies, you no longer have Monsieur Fouquet. But here is the Superintendent. Am I not bringing a body just as well suited as his to please you? And moreover I am king.”

[ Le Roy entrant un de ces jours dans le cercle des dames, et voulant faire le Galant, leur dit hé bien mes dames vous n'avez plus Monsieur Fouquet, mais voici le Surintendant n’ai-je pas un Corps aussy bien fait que le sien pour vous contenter, et de plus je suis Roy.]

The scene is thus set for an excursion into occasional verse. This fragment begins with the admonition, “Montfaucon is calling him!” referring to the traditional (and long abandoned) execution place for enemies of the regime, and Monseigneur Enguerrand de Marigny, executed there in the fifteenth century. Then:

My dear Fouquet, the court is importune

Enguerrand waits, your turn has come at last

In spite of much faveur, and much fortune,

In the end you’ll have to fall feet first.

[Montfaucon l’appelle

Venez mon cher Fouquet la cour est importune

Enguerrand vous attend, c’est pour vous l’autre bout

après tant de faveur, après tant de fortune

vous ne pouvez enfin plus tomber que de bout.]

Admittedly, our version requires some translators’ licence, about which, look for more in our upcoming Featured Post on “Lost In Translation.”

FURTHER READING:

Pierre Goubert, Mazarin, Paris, Fayard, 1990

Marc Fumaroli, Critique et création littéraire en France au XVIIe siècle, Paris, Éditions du C.N.R.S., 1977

Jean Rohou, Le Classicisme, Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2004.

Toni Marcus, “‘L'innocence Persecutee’ (c 1665) One Polemicist's Perception of Contemporary Politics,” Seventeenth-Century French Studies, 13/1 (1991), 71-89

Pascal Debailly, “Nicolas Boileau et la Querelle des Satires,” Littératures classiques 68 (2009), 131-144