“The mail from Milan which arrived on Thursday evening said that they burned one of the witches they had in jail, who among other nefarious deeds confessed to having perpetrated 150 homicides of little children.”

An appalling indictment, described in this Rome newsletter of 30 August 1603 with the typical economy of words that characterized the genre. The account goes on. Such an awful slaughter of the innocents occurred because of an agreement whereby the accused “promised to give one per week to the devil.” (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Urb.lat.1071.pt.2, 430v)

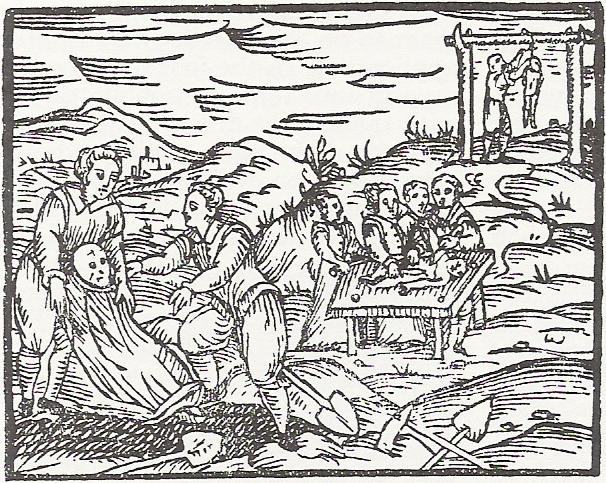

Below: engraving from Compendium maleficarum by Francesco Maria Guazzo, Milan: 1608

Archbishop Federico Borromeo, already well on the way to matching his elder cousin and predecessor, Saint Charles Borromeo, in severity if not in holiness, sought to ensure that Milan was no safe haven for devilry; and just three months before, Isabella Arienti, called la Fabene, and Gabbana la Montina, were executed for witchcraft along with numerous others whose names have been erased by the destruction of documents.

The court knew how to get what was necessary. The Spanish Inquisition set up in Milan a half-century before by Philip II could boast a long record of dealing sternly with heretics, Protestants, blasphemers, conversos, marranos, and any other suspect individuals, between Milan and Madrid.

No wonder that among the special guides for inquisitors, closer to our place and dates than Heinrich Kramer’s notorious Malleus Maleficarum (1486), was the Compendium maleficarum by Francesco Maria Guazzo, published in Milan in 1608, which specified, possibly using the experiences we have just recounted, that witches “pollicentur sacrifica, et quaedam striges promittunt se singulis mensibus, vel quindenis unum infantulum strigando” (Guaccio, 1624: 40), i.e., witches pledge sacrifices to the devil, and some promise to strangle one infant every month or fortnight. In the case at hand by this standard we can observe a particularly energetic witch. Or perhaps, particularly energetic inquisitors.

If confession was called the queen of proofs, in this era before legal forensics and the Enlightenment trend exemplified by Cesare Beccaria, torture was the king of interrogation methods--fast and efficient. Matching a few suspects to a few crimes, at least according to Michel Foucault’s provocative interpretation of criminology in premodern times, was less important than instilling widespread fear of detection and the awe of power. Enough that the criminal should have one or more of the characteristics of a possibly suspicious person: unruly, unattached, foreign, of non Christian affiliation, belonging to a minority, and in the case in point, female.

Interrogations developed over time in tandem with the information being provided by indicted persons. Apart from pledging babies to the devil for sacrifice, other witch activities were believed to be nocturnal air travel, banquets of human flesh, etc.

According to the so-called Witch Cult Hypothesis, modified and relaunched by Carlo Ginzburg on the basis of documents from Friuli, the behavior and mythologies that incited at least some witchcraft accusations were actually the feeble modern survivals of ancient fertility cults, once prevalent, but lately hounded into oblivion by zealous defenders of the Christian credo, interpreting pagan euphoria as diabolical malice.

After the intermittent European witch craze was practically over, witch hunts got a new life in the new world. In Salem, Massachusetts, at the end of the century no fewer than 200 accusations and thirty convictions occurred in an environment where Puritan settlers worried about the dangers everywhere lurking in an unholy land.

Apart from the usual features attributed to witches and admitted under duress by those interrogated, the Salem court was particularly convinced by what was called “spectral evidence,” i.e., attestations by community members that they had seen spectres in the neighborhood bearing the features of the accused, which according to the impeccable logic propounded for instance by the English jurist Sir Matthew Hale, could only occur if the accused persons had permitted the nefarious use of their features by the devil for harmful purposes, perhaps in a premodern instance of the now-prevalent granting of rights that appears on our screens when visiting innumerable websites for work or play.

But that, as they say, is another story!

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carlo Ginzburg, Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches' Sabbath, tr. Raymond Rosenthal, NY: Random House, 1991

Walter Stephens, Demon Lovers: Witchcraft, Sex, and the Crisis of Belief, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002

Mary Beth Norton, In the Devil's Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692. NY: Random House, 2002

Storia di Milano, 20 vols., vol. 10: L'età della Riforma cattolica (1559- 1630). Milan: Fondazione Treccani degli Alfieri per la Storia di Milano, 1957, pp. 298-302.

and thanks to Dr. Miranda Corcoran