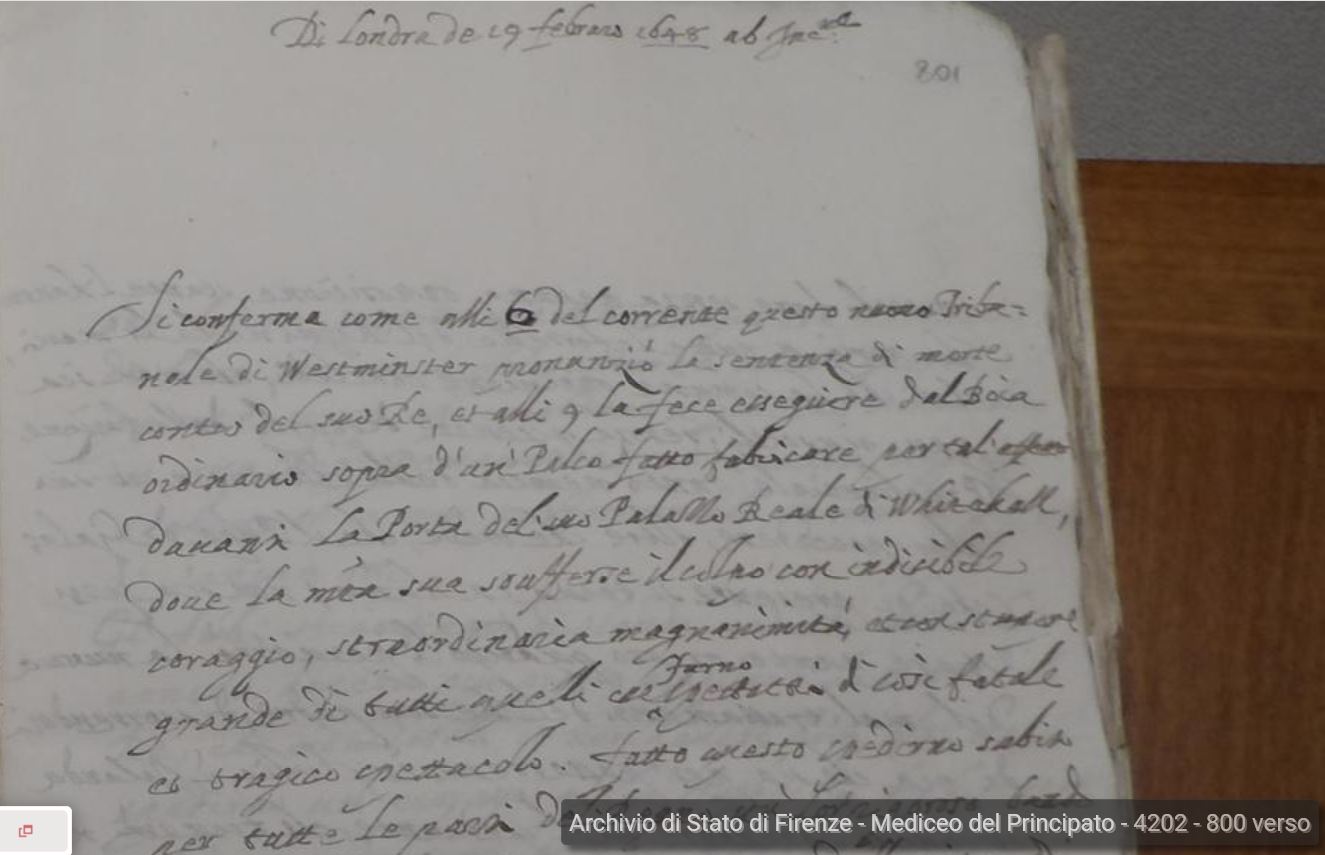

In the words of the Florentine resident, Amerigo Salvetti: “It is confirmed that on the 6th of this month this new tribunal of Westminster pronounced the death sentence against their king, and on the 9th had this carried out by the ordinary executioner on a specially made stage before his royal palace of Whitehall, where His Majesty suffered the blow with unbelievable courage, extraordinary magnanimity and amid the general astonishment of all the spectators of this fatal and tragic spectacle.”

The astounding news about the execution of King Charles I arrived in the Tuscan court, and wherever else Salvetti’s London newsletter (dated 19 February 1648/9) was transmitted, recounting the latest episode in an ongoing civil war that brought about a regime change, confirming the hopes of many, and the fears others in England and abroad. The media frenzy generated by the events would be felt as far away as Naples. (Boerio, 2016)

LONDON TO FLORENCE

MdP 4202, fol. 801r

Getting the word back quickly to the people at home was the crucial role of diplomats in England from each place, as the events unfolded. But not only. Based on whatever sources were available including the newsletters, a diverse range of print publications set out to inform, and, often under precise instruction from administrators, to direct the conversation.

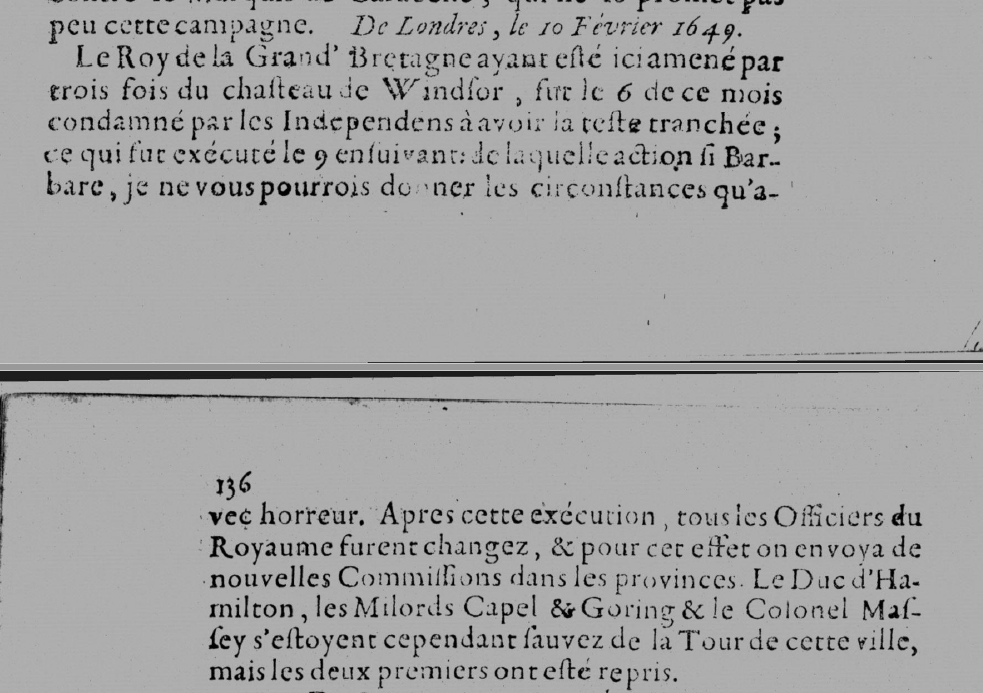

LONDON? TO PARIS

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6443617j/f1.item

Salvetti was not alone in his indignation. Théophraste Renaudot, author of the Paris Gazette, displayed some sentiments similar to Salvetti’s, remarking “The king of Great Britain having been brought here three times from Windsor Castle, was on the 6th of this month condemned by the Independents to have his head chopped off; which was done on the 9th,” said a report from London published in the French Gazette on 27 February 1649 (new style). The writer added, “I cannot provide the details” of the king’s execution “except with horror.”

PARIS TO TURIN

As the news went round the world of seventeenth-century media, the Turin newspaper called Successi del mondo, among the first such papers in Italy, picked up the story, with the author and publisher (Pietro Socini) adding various elements of analysis and dramatic effect. For instance, “The scaffold was prepared before the royal palace in order to heighten the outrage.” Moreover, “The diplomatic corps, alarmed about the hasty decision, especially the French ambassador, tried to avoid a tragedy; but they were not even allowed to speak.” The writer seems overwhelmed by what is occurring, to the extent that "my pen falls from my hand, and I seem scarcely able to arrive at the catastrophe of that bloody tragedy. A king, the best king in the world, is drawn like a lamb to the slaughter.” (quoted in Jovane, 1938).

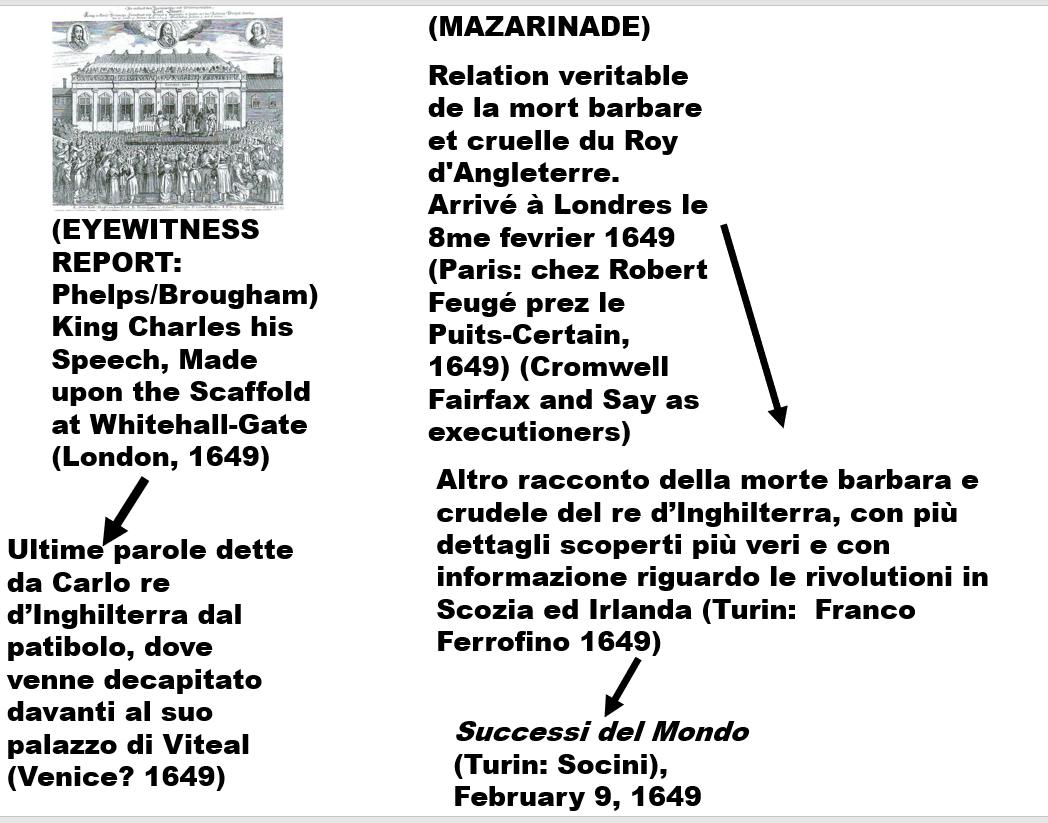

Indeed, in the stories we have been discussing, the expressed sentiments of the writers are occasionally borrowed from yet others. In compiling the account in the Turin paper, for instance, the writer took much of the commentary word for word from a pamphlet previously printed by another Turin publisher (Franco Ferrofino) entitled Altro racconto della morte barbara e crudele del re d’Inghilterra, con più dettagli scoperti più veri e con informazione riguardo le rivolutioni in Scozia ed Irlanda (Another Account of the Barbarous and Cruel Death of the King of England, with Greater Details Found to be Truer, and with Information Concerning the Revolutions in Scotland and Ireland). Cuts were required also due to the difference in genres, so on the way from Ferrofino’s pamphlet to Socini’s newspaper something is lost and, arguably, something is gained.

FERROFINO

My pen falls from my hand, and I am seized and possessed by such horror that I seem scarcely able to arrive at the catastrophe of this bloody tragedy. The king, the best king in the world, is drawn like a lamb to the slaughter, and subject to these barbarous arms to quench their rage and their furor. He is taken from his prison to the place prepared for this execrable act, and there he walks, unconstrained, and Death cannot efface his sacred visage, the living image of God, to replace it with his own.

SOCINI

My pen falls from my hand, and I seem scarcely able to arrive at the catastrophe of that bloody tragedy. A king , the best king in the world, is drawn like a lamb to the slaughter. He asks to speak to the Parliament, but the executioners forbid him. The hangmen however were too horrified to proceed to the execution and refused.

Traitors and rebels, sate yourselves with my blood.

Yet even Ferrofino’s were borrowed tears, deriving in fact from a royalist pamphlet from the French civil wars collectively known as the Fronde, and therefore collected in the miscellanies called Mazarinades although evidently somewhat out of harmony with the generally anti-establishment bias of the genre. Its title: Relation veritable de la mort barbare et cruelle du Roy d'Angleterre. Arrivé à Londres le 8me fevrier 1649 (Paris: Robert Feugé, 1649). Common to both was the hilarious trope, according to which the executioner feared and fled, whereupon Cromwell, Fairfax and Lord Say dressed up for the part and carried out the decapitation.

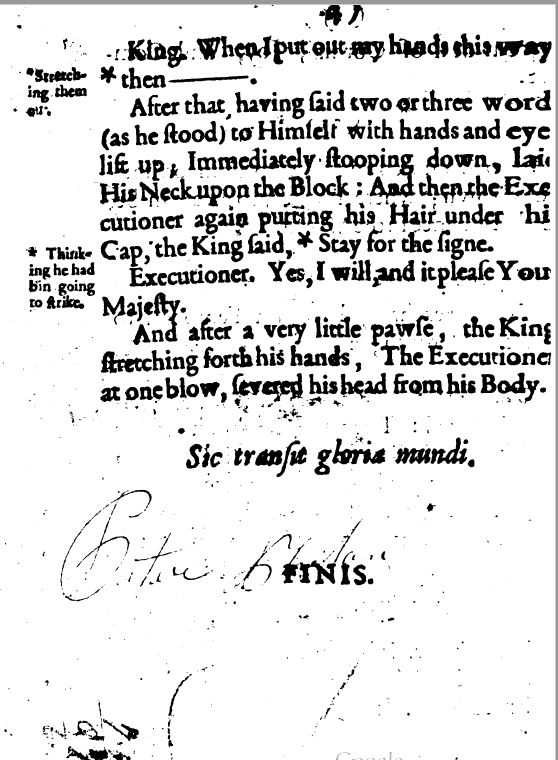

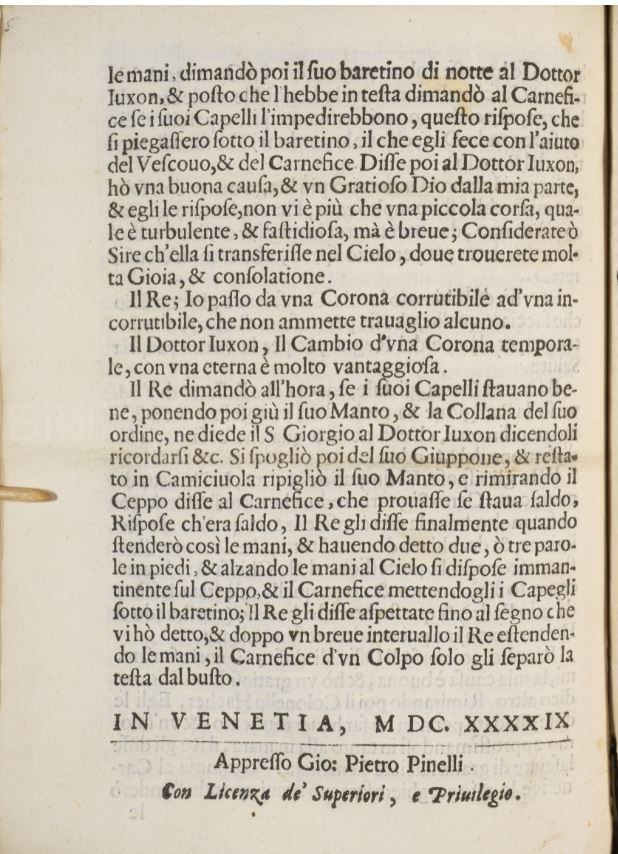

While the Turin paper relied on the Mazarinade, a pamphlet printed in Venice relied instead on a tract entitled King Charles his Speech on the Scaffold, published within hours of the event, which relied (so it claimed) on information from "some gentlemen that wrote," apparently the two clerks of the court, Phelps and Broughton. The Italian version modified the time to suit the Continental clock (10 AM becomes 17 Hours), the date to correspond to the Gregorian calendar (January 30, 1648 becomes February 9, 1649). One more crucial textual change apparently accompanied the change of place, as seen below.

Where the English original ended with the philosophical reflection, “sic transit gloria mundi,” thus passes the glory of the world, instead we find the statement that this printing is “by licence and privilege of those in charge,” as if to remind that killing rulers, in a government by one or by many, was never to be taken lightly, and no business of the plebs (Messina, 1984; Dooley, 1999).

We can thus diagram the two paths of news thus:

This at least is what we have been able to discover so far. No doubt, much more will turn up as we sift through the papers at the birth of news!

REFERENCES

Enrico Jovane, Il primo giornalismo Torinese, Di Modica, 1938

Pietro Messina, "La rivoluzione inglese e la storiografia italiana del Seicento," Studi storici 25 (1984): 725-46.

Brendan Dooley, The Social History of Skepticism: Experience and Doubt in Early Modern Culture, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999

Stéphane Haffmayer, L’information dans la France du xvii e siècle : La Gazette de Renaudot de 1647 à 1663 (Paris: Honoré Champion, 2002)

Davide Boerio, "The ‘Trouble of Naples’ in the Political Information Arena of the

English Revolution," in Joad Raymond and Noah Moxham (eds.) News Network in Early Modern Europe (Leiden: Brill, 2016), 779-804.