The Irish were making trouble again, or so it seemed. The year was 1666, and relations between the Irish and the English, only recently becalmed following the close of the tumultuous Cromwellian period, were being roiled by a new crisis, this one having to do with large landowners and their exports. The beef? This time, of the bovine kind.

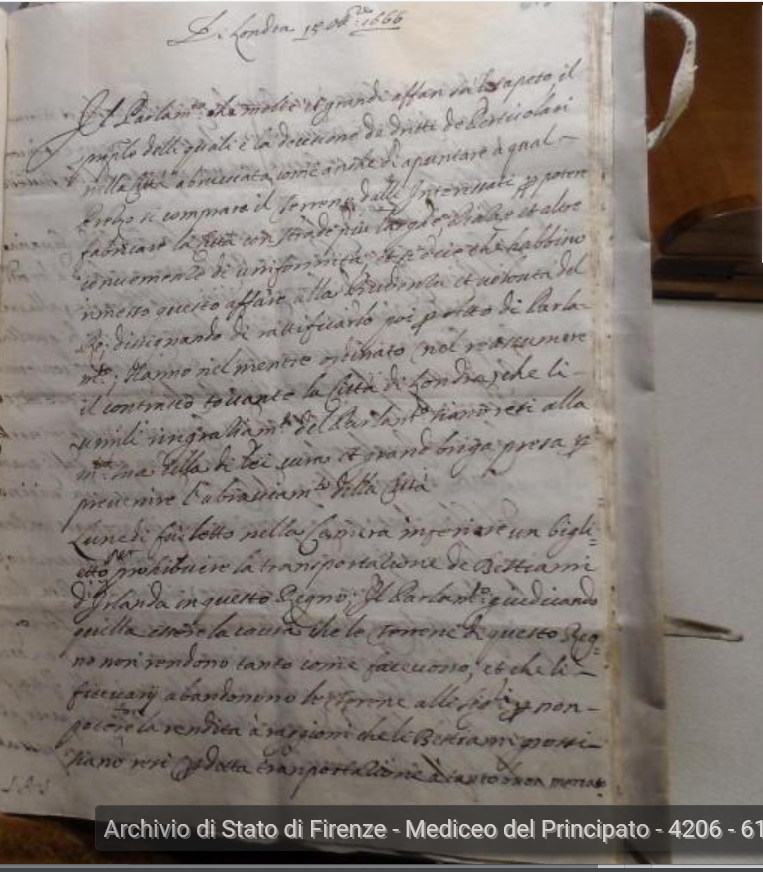

According to the Italian-language newsletter from London, “Monday there was read in the Lower House a bill [biglietto] to forbid the transport of Irish livestock into this realm; the Parliament judging this to be the reason why the land in this kingdom does not yield what it once did.”

Giovanni Salvetti Antelminelli, the Tuscan resident diplomat in London during the Great Fire of 1666, had a lot on his mind in that fateful year-- including the need to save his own skin (for which purpose he absconded for a time to a suburb of the metropolis). But during the entire disturbing period he continued his commitment to keep the Tuscan court, and Grand Duke Ferdinand II, informed about events in that somewhat remote part of the world, several seas and lands away. His newsletter “di Londra,” of which copies may have circulated beyond the principle addressees although none others have yet come to light, was a labor of love and devotion as well as a likely essential part of his legacy. Indeed, the whole corpus would be transcribed in the nineteenth century, and later filed in the British Library, in view of a proposed and then abandoned edition.

[MdP vol. 4206, fol. 617r, https://mia.medici.org/Mia/index.html#/mia/document-entity/52097]

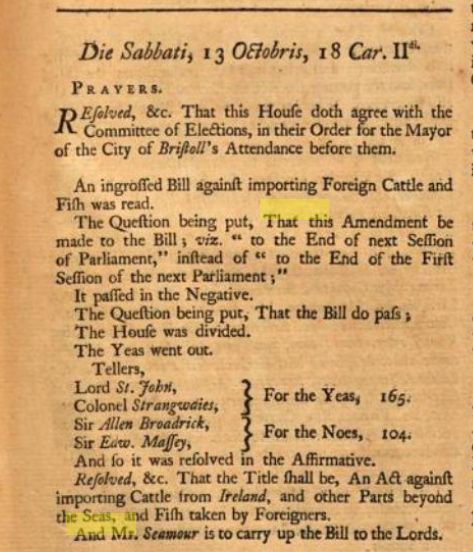

Whatever the London Gazette, the government’s official newspaper, edited by the Secretary of State, may have published regarding the Irish matter (and there is little sign that at least in this particular moment there was much at all), nonetheless, the Journal of the House of Commons returned frequently to the issue, due to what were viewed as the enormous repercussions for the English gentry, i.e., a chief constituency of the Parliament, many of whose substantial incomes and significant obligations were founded on the sale of livestock grazing on their lands.

In the example below, a suggestion is accepted, that the bill should finally be explicit about the contents, such that the “Bill against importing Foreign Cattle and Fish” should be named for what it was, “An Act against importing Cattle from Ireland, and other parts beyond the Seas, and Fish taken by Foreigners.”

Salvetti understood what was going on, at least economically, as well as did the Parliament members and their constituents. “Renters abandon their lords because unable to pay rent since large livestock have become so cheap due to this importation.”

The laws of supply and demand were no mystery in the late seventeenth century, as the practices of mercantilism got well under way.

Salvetti continued: “The said Bill having been read already a second time is sent to a Committee [Committi] to examine the conveniences and inconveniences and report the result to the Parliament.” The significance of this hotly contested theme went far beyond the controversial ‘Cattle Acts’ that came as a direct consequence. With the king somewhat lukewarm to a question that seemed possibly damaging to the interests of a part of his realm, but a major faction within Parliament set on casting Ireland as an external entity upsetting the balance of trade, a power struggle was in the making, on both sides of the Irish Sea as well as between Whitehall and Westminster. In subsequent years, so we are informed by the recent scholarship, the eventual Acts, as passed, would provoke a fundamental transformation of the Irish landscape from grazing to grains, with definitely unforeseen and unintended (though sometimes positive) economic consequences. No wonder the issue galvanized factions on all sides.

FURTHER READING

On Irish-English relations in the period, Ted McCormick, ‘Restoration Ireland: 1660-88’, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Irish History, Alvin Jackson, ed. (Oxford: 2014), chap. 18; as well as Jacqueline Rose, Godly Kingship in Restoration England: The Politics of The Royal Supremacy (Cambridge: 2011), 91-2. Also relevant, Donald Woodward, ‘The Anglo-Irish Livestock Trade of the Seventeenth Century’, Irish Historical Studies, 18, No. 72 (1973), 489-523.

On Salvetti and his newsletters, see the forthcoming article by B. Dooley and Davide Boerio, “Hot News! The Florentine Resident Reports on the Great Fire of London,” Parliamentary History, with relevant bibliography. In addition, Stefano Villani, 'Per la progettata edizione della corrispondenza dei rappresentanti toscani a Londra: Amerigo Salvetti e Giovanni Salvetti Antelminelli durante il "Commonwealth" e il Protettorato (1649-1660)', Archivio Storico Italiano Vol. 162, No. 1 (599) (gennaio-marzo 2004), pp. 109-125.