Sometimes the wrapping is almost as curious as the item itself.

In the case of vol. 4028a of the Mediceo del Principato collection at the Archivio di Stato in Florence, the 700 or so folios of handwritten newsletters stored here, mostly from Rome in the 1640s, are divided into seven groups of roughly a hundred folios apiece, contained in seven individual folders or wrappings, blue in color and evidently recycled, having been turned inside out so that the former archival indications from a previous usage are on the inside back cover rather than on the front. All are dated 1874, and all have a brief indication, partly printed or stenciled, and partly handwritten, of what they once contained. For instance, on the back inside cover of the fourth fascicle, following a newsletter dated Rome, 31 December 1643, we find this inscription: “1874: Affare 2970; categoria 6, Ogetto: lesioni casuali riportate da Vincenzo degli Innocenti.” Again, in the same place on the cover of the fifth fascicle, following a newsletter from Rome dated exactly one year later, we find, “Affare 2971; categoria 6, Ogetto: lesioni casuali riportate da Baldassini Carlo.”

We are led to surmise that both of these evident cases of violence, brought to the attention of the municipal authorities of the former capital of unified Italy and resolved in ways we are not at present able to discover, must have formed part of a more extensive collection of such documents in the collection of police records. The records, say our friends at the State Archives in Florence, were subjected to the somewhat arbitrary elimination of files carried out during the Fascist regime, on the basis of then-accepted criteria of what was useful and what was not. In the latter connection we are tempted to agree with the view of Antonino Lombardo in a 1955 article published in Rassegna degli Archivi di Stato, criticizing any narrowly conceived notion of utility, because “a writing might normally be considered useless but acquires a new interest if written in a particular moment or by or about a particular person. Likewise a document may be useless in a situation where there are many other sources, but precious in extraordinary circumstances (wars, fires, earthquakes).” We would even add, wrappers too may tell stories!

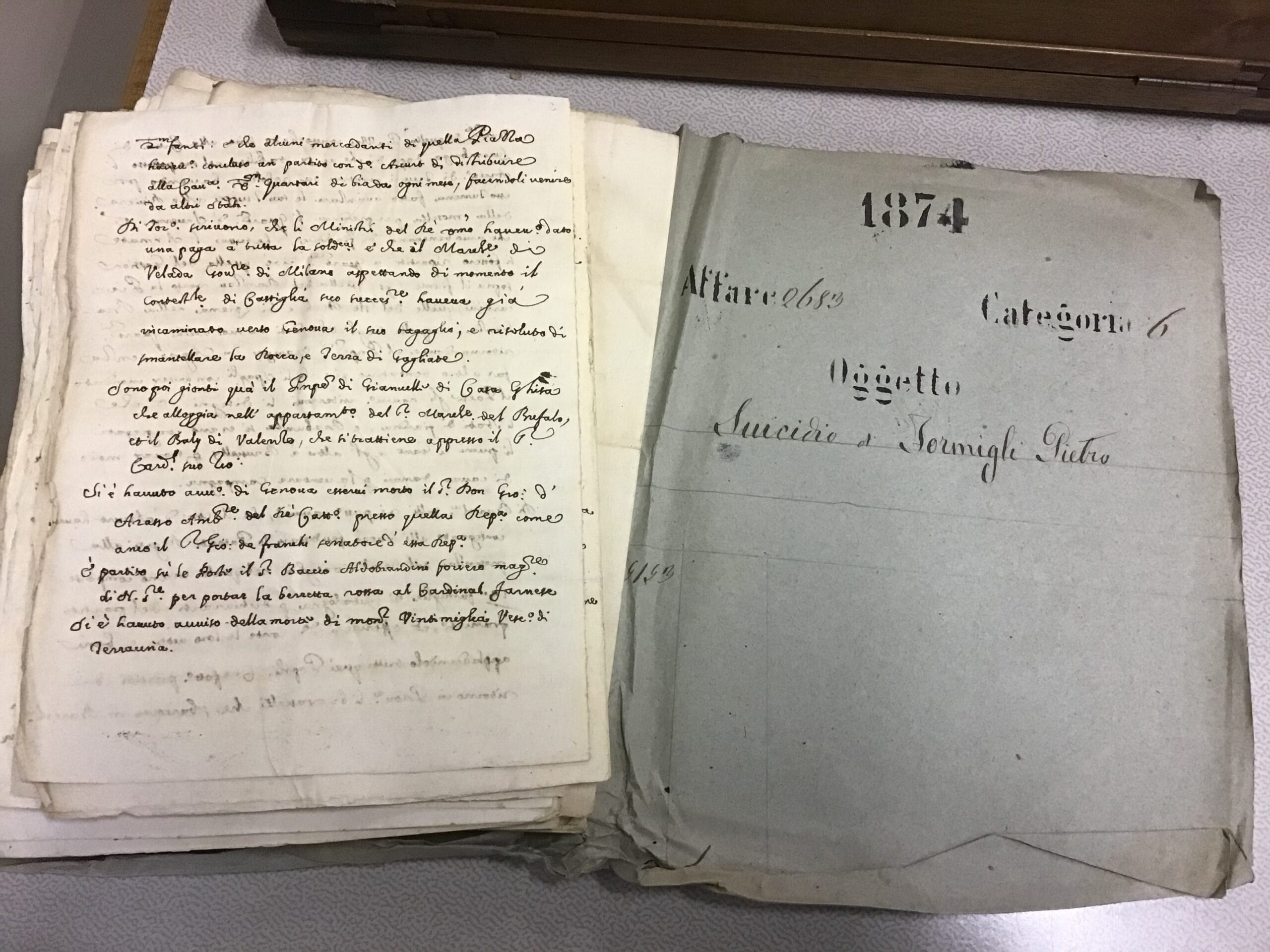

In any case, our attention fixes on the sixth fascicle in this series, following folio 635 verso, which is part of an avviso from Rome dated 30 December 1645, where we read about “1874: Affare 2683; categoria 6, Ogetto: suicidio di Formigli Pietro,” i.e., the suicide of Pietro Formigli. Here is the relevant page, on the right:

As suicide is not a common phenomenon in any society, and the historiography of this period leaves it out (Denis Mack Smith, etc. etc. etc.) we wonder: who was this Formigli Pietro and why did he resort to the ultimate act of desperation?

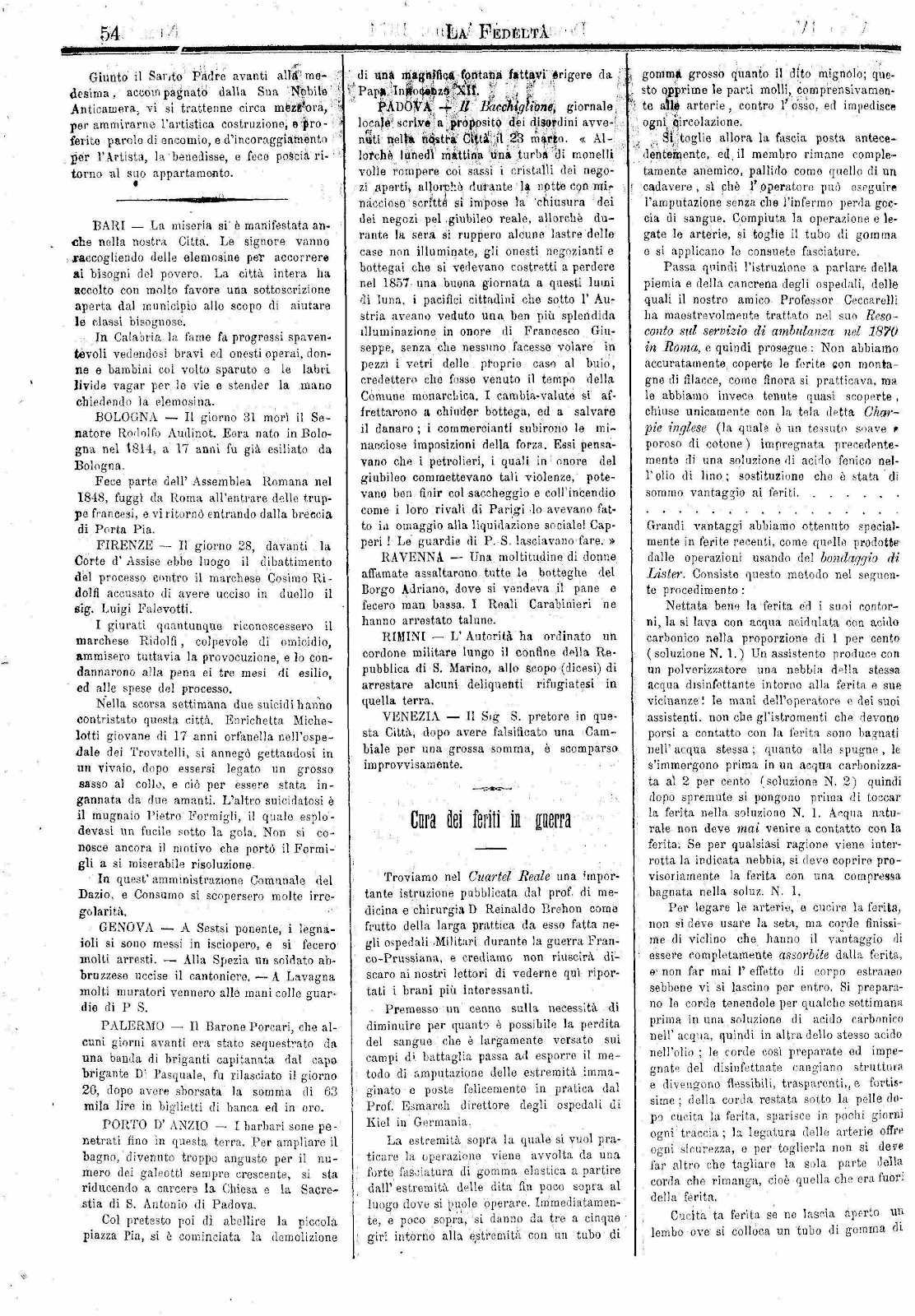

The case did not go entirely unnoticed in the press. In the April 6 edition of La Fedeltà, the periodical of the Vatican war veterans’ association, a column devoted to news from Florence features this story:

It says, “In the past week two suicides have saddened the city. Enrichetta Michelotti, a 17 year old orphan at the foundlings home, drowned by throwing herself into a hatchery after fastening a large stone around her neck because she had been betrayed by two lovers. The other suicide was the miller Pietro Formigli, who shot himself in the throat with a rifle. The motive that brought Formigli to such a sad decision is still unknown.”

True, the Enlightenment decriminalized suicide, and Romanticism gave it new heroes. But the relative infrequency of the phenomenon, and the difficulty of finding sources that speak to the psychic states of people in the past, which appear to be relevant in such cases, with the exception of a few individuals located within high culture, who have left shall we say a paper trail allowing access where usually there is none, continues to provide a credible rationale as to why this kind of experience gets short shrift. Nonetheless, our natural curiosity combined with the need for answers to important comparative questions about life in various times, urges the formation of hypotheses even when the evidence is thin.

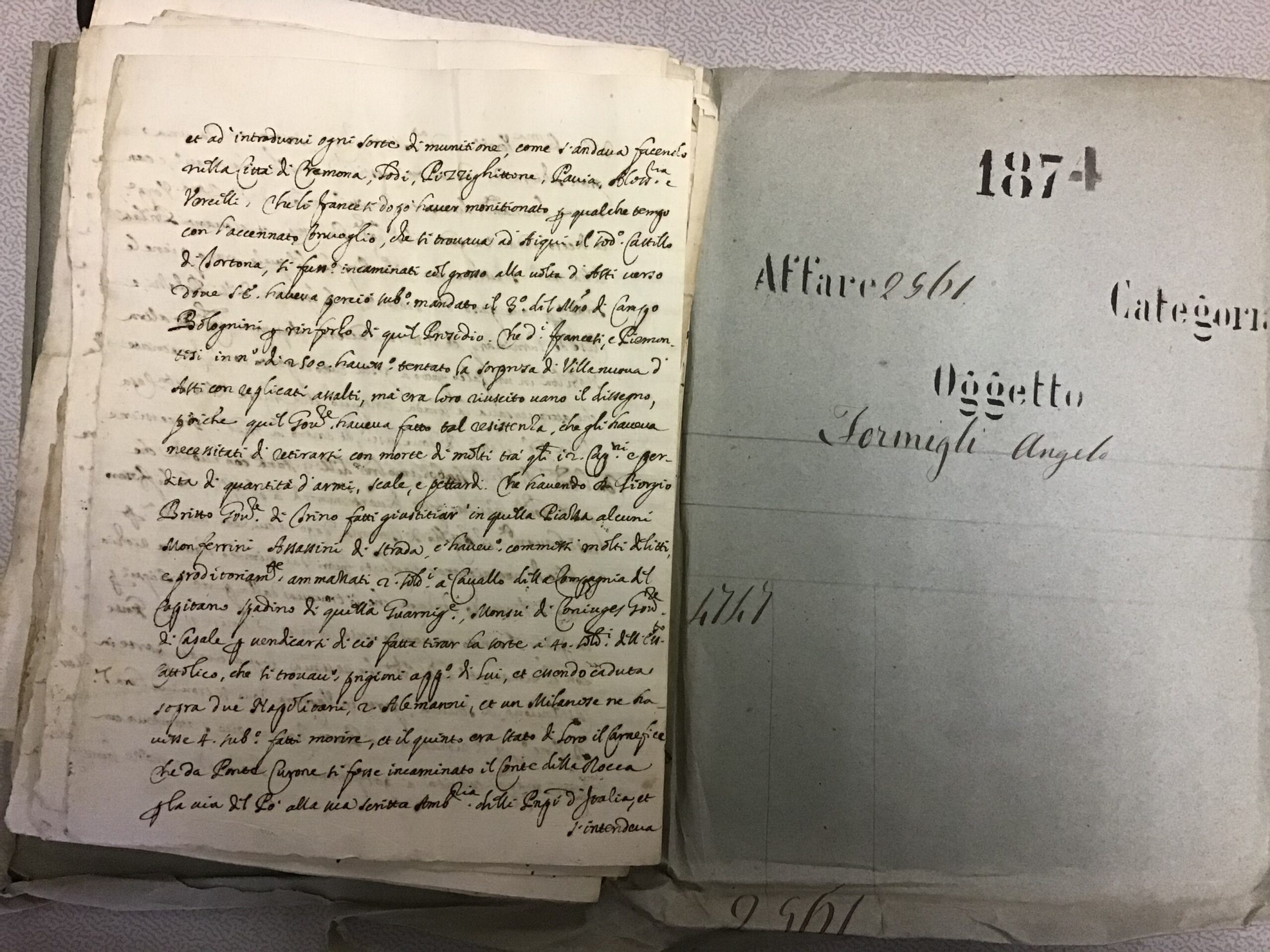

For instance, in this case, rereading the phrase that has caught our attention, we recall the wrapper inscription from a few pages back, namely, on the back inside cover of fascicle three, where we read, “Affare 2961, Ogetto: Formigli Angelo”. A family member of our unfortunate suicide, arrested for some still undiscovered crime? Is family disgrace a sufficient cause for ending one’s life?

But any speculation about the so-called reasons for suicide inevitably runs up against the founding text of suicide studies, and of modern sociology, Émile Durkheim’s pathbreaking work, Suicide, published twenty years after the events mentioned on our wrappings, using data from more or less the same period. There we discover that, for instance, suicide was comparatively rare in Italy, possibly, the author hypothesizes, due to the integrated structures of church and family offering help and solidarity to those in psychic need. However, the surprising results, for readers at the time, were the statistics pointing to the rate of suicide over a number of years, constant in each country but differing from place to place, apparently according to the different sociocultural structure of each.

What do suicide studies have to do with the history of news? One answer could be that here, as there, we are interested in the bigger picture, however curious we may be about the individual stories recounted in our documents. Indeed, our evidence so far confirms the basic axiom of sociology--namely, that humanity is dual: a part belonging to the ways of the self, and a part belonging to the ways of the group. News reporting, while conveying details about single experiences and contributing to a growing market for information, also answers a basic need for society to come to terms with the vicissitudes of fortune, the extreme trends, and the threats to systemic survival that, left unchecked or modulated, may exact a sacrifice from the most vulnerable or those with no protection. Our object is to discover when and how.

Many thanks to Dr. Antonio Tanturli and Director Dr. Sabina Magrini at the Florence Archivio di Stato for their suggestions.

FURTHER READING

Émile Durkheim, Le Suicide: Étude de sociologie, Paris, Félix Alcan, 1897

P. Steiner, La sociologie de Durkheim, Paris, La découverte, 2000

Marcel Fournier, Émile Durkheim: 1858-1917, Paris, Fayard, 2007

W.S.F. Pickering, Geoffrey Walford, eds., Durkheim's Suicide: A Century of Research and Debate, Abingdon, Routledge, 2000.

Georges Minois, History of Suicide: Voluntary Death in Western Culture, tr. Lydia G. Cochrane (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999)

Antonino Lombardo, “Il problema dello scarto degli atti di archivio,” Rassegna degli Archivi di Stato 15/3 (1955): 300-316