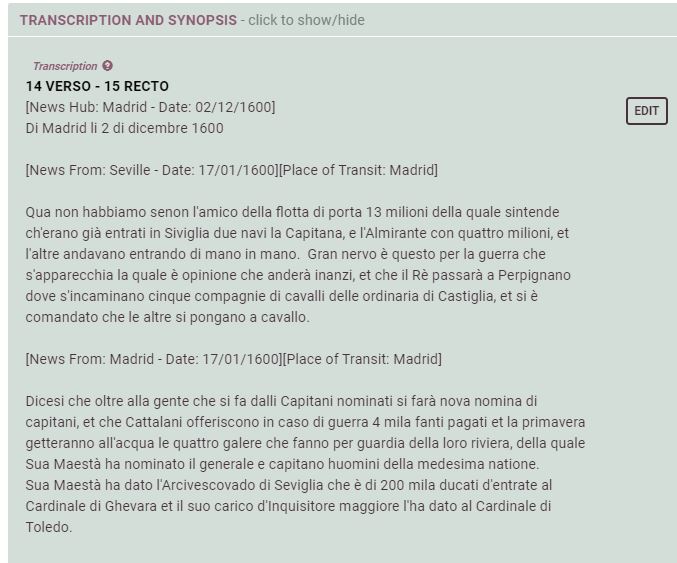

Shocking news from Hungary: according to a source in Graz writing on January 17 1600, “By the last letters . . . there is a report that Ibrahim Bassa, after having strangled the chief of the Tatars, as was already known, headed from Belgrade to Constantinople, where exactly at that time there arrived another Tatar from the same family, claiming to be the successor of the deceased.” The new pretendant to Tatar leadership was moving quickly. At least according to the report, with Turkish support he was gathering the whole horde together and heading out of Hungary in order to invade again with a bigger force in the following year.

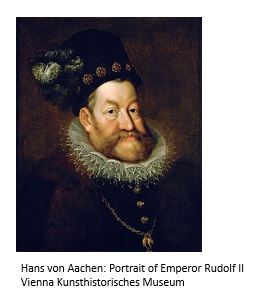

We uncovered this data during a preliminary analysis, recently concluded, of a body of original manuscript news material from the year 1600. Regarding the information in this particular newsletter, the consequences for Europe were inestimable at the time, and even more so considering that they were not yet known: the Long Turkish War still had no name, even though the Battle of Mirăslău would soon aggravate matters; the 1602 siege of Buda had not yet taken place, the second in four years; Sultan Mehmet III was still alive. Rudolf II was still the emperor and István Bocskai had not yet roiled the realm by leading a rebellion in Hungary and Transylvania.

But who was this new Tatar, and when the standard sources seem unhelpful for answering our questions about specific events that may or may not have occurred exactly in the way narrated in the news, what recourse do we have? Indeed, that is not even the chief problem in this study of the ways and means of communicating about current events in the year 1600 as seen from the standpoint of the Tuscan grand duchy. How much news was there? Where did the news come from and where did it go? How did it travel? And when it reached destination what were the possible effects?

Questions down the line will call for digging deeply into the culture of early modern cities, and not just Florence. Many of our answers will have to be highly speculative. What was the view shared by Florentines, for instance, in regard to the world outside, and how can we grasp this by looking at how they talked about what they thought they knew? What was their perception of the passage of time? What other sources would we need to go beyond the vaguest answers?

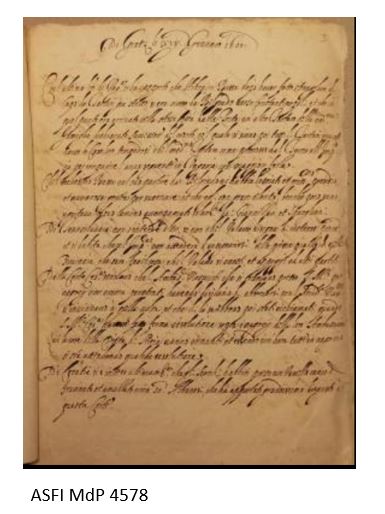

To suggest an approach to some of these and still other questions the EURONEWS project has tapped into a vast resource: all the news documents present in the Mediceo del Principato collection within the Florence State Archives, amounting to some 200 volumes of material covering the period from the early sixteenth to the early eighteenth centuries. Regarding the year 1600 alone we find a wealth of documentation, whereas the bulk of material in these volumes is from later in the century. Though limited in quantity, we have taken a sampling from this specific year in order to test our methods and draw some advance conclusions, as we will show in another post!

One thought on “THE 1600 EXPERIMENT: PRELIMINARY REPORT”